11.1 – The big bang: birth of the pure artistic phenomenon

We shall attempt to analyse the human being’s greatest moment, when creativity comes into play. It should be noted that there are different “degrees of creativity”, in accordance with mind-brain-nervous system involvement. Beginning with the lowest form, we can identify:

- Purely rational (or rational-re-working) creativity. Only autonomous, automatic mental elaborations play a part, in the guise of logical (philosophy), logical-numerical-computational (mathematics) and logical-structural (physics, chemistry and science in general) statements. In this sector realisations do not require “emotions”, everything following planned development, as it were. It should be borne in mind, however, that none of the great, fundamental “intuitions” of science and the arts have been achieved with this kind of creativity. Nevertheless, these intuitions need to be expressed and are slavishly and analytically re-formulated by the human mind with methodologies proper to this sector.

- Rational-re-working creativity. The rational human mind, apart from autonomous elaborations, can now access re-working faculties applicable to emotional archetypes contained in the dispositional representations realised by both innate and modifiable neural circuits, which are inter-connected and linked to the learning centres by way of more or less “strong” synapses. This kind of creativity is mainly to be found in literature in general, theatre, “standard”, conventional parts of poetry, music and the other arts and, in language, emotional phrases, though exposed with purely rational canons, come into play, as well as logical-numerical-structural ones. In this sector re-worked expressions of pure emotional, expanded and composite archetypes, but never original emotional archetypal expression.

- Archetypal creativity. This is sparked off by the mechanism we called the “big bang”, the great explosion or “flash of sudden awareness” in the subconscious, which spreads through the human being, embraces and makes use of every corner, of the nervous system, viscera and limbs, involving both the neuronic structures in groups (of the subcortical area) and the more recent ones with stratiform structures (palaeo- and neocortices). The pure emotional, expanded and composite archetypes present in the respective dispositional representations come to the fore and are used by an unknown mechanism. They are embedded, as it were, in a great composition and re-appear at the conscious level, in a totally original sequence of integration, different on each occasion.

Great Art, like Great Science, comes to life with a core made up of emotional archetypal expressions. It is flanked by re-worked expressions attempting to soundly enclose the a-logical and untypical explosions in logic. The artist’s function is a delicate one as he/she is first called upon to feel and then mediate. His/her greatness consists in finding “supreme balance” between the various expressions. But let us have a closer look in whom, how and where the “big-bang” comes to life. The reason for its existence has already been adequately described. We should recall that homo sapiens has always created “art”, even before having a fully structured mind, and (luckily!) kept this faculty even when the rational mind formed its “stranglehold”. Being unable “to understand” emotions constitutionally, the human rational mind could only “logically organise” its reflexes contained in neuronic representational dispositions, waiting for the “liberation” of the self expression mechanism of the great original emotions, which, at the outset (in primitive beings and babies) was always active, and now (in today’s adults) was repressed and conditioned for specific situations and, probably, people. But what situations and what people? Let us set aside, for the moment, the analysis of normal situations and people and look at extraordinary ones. The great artist in an extraordinary situation is an extraordinary person. We should recall that he/she only rarely participates in this situation, which only takes place when, following long, deep-rooted concentration, he/she attempts to collect and synthesise (in part rationally and in part intuitively) the most hidden motives and contents of his/her “feeling”. This is when “rapture”, “a sudden flash of awareness”, a “big bang” is reached, removing all consciousness and rational possibility of “immediate action”, forcing him/her to listen to him/herself unawares. Those who have had this experience describe it as a state of supreme completeness, together with supreme joy and suffering, at the end of which, in anguish and exaltation, consciousness is re-acquired. At last we will find there a concrete trace of the great archetypes, arranged so as to unambiguously and originally represent those “motives” present in the concentration preceding the big bang. Now, at last, consciousness will slowly pass from being intuitive to rationality and will be able to take charge of the great archetypes, almost Tables of the Law, which a new Moses has found himself in his hands, mysteriously written! But after the concentration preceding every great artistic event, how is the creative process issuing from the big bang activated in the artist? As he/she needs to evoke and articulate an emotion in ever more real terms, the self-conscious individual activates, by means of both the rational and unconscious mind, by-pass circuits including dispositional representations linked with ever more “external” organs ever closer to the skin, the body contour. The process can go as far as including the very senses, and thus the neural circuit is no longer “by-pass”, but the whole nervous system, neural circuits included (piloted by the cerebellum) connected with the subconscious. This takes place in some moments of “inspiration” where bodily involvement becomes total and the rational mind is temporarily “put to sleep” in “stand-by”. Where does the artistic big bang come from? From outside or inside the mind? How can we be sure that it is not an exclusively rational product? We shall see that, before mental re-workings by cognitive brain structures come into the picture, the big bang appears as an intense emotion pervading the whole mind-body complex. But if it had an external bodily origin in respect of the conscious rational mind, it would be perceived before by the senses, like every usual physical-sensory-emotional stimulus picked up by the mind through the senses and catalogued in the relevant dispositional representations of the neural circuits, and this does not happen. If, on the other hand, it were to explode within, we would have to conclude that the conscious rational mind is able to “create” emotions (instead of only perceiving them by means of the senses, cataloguing, recalling or re-working them), and this is not true either. So it should be deduced that the big bang takes place in a cerebral area which is both outside and inside the conscious mind-body complex, i.e. in the subconscious, which during “rapture” functions autonomously along the path of the contents of previous deep-rooted concentration. In the end the result of this activity becomes emotionally perceivable by human consciousness (and immediately afterwards by the rational mind) by means of a modifiable neural circuit (of hitherto unknown identity) connected to the subconscious, able to fix the “emotional visions” due to the big bang in particular dispositional representations. As we said, the big bang was caused by “deep-rooted concentration” linking the various, specific by pass circuits required to reawaken the various dispositional representations in the artist’s nervous system, inter-connecting them so as to “make available” to his/her subconscious all the different types (and degrees) of emotion in him/her, in some way linked to the sought after artistic event through deep-rooted concentration.

At this point we have the “awakening” of the rational mind, which is now in an ideal position to be able to begin re-working of all the material contained in the above mentioned modifiable neural circuit transmitted by the subconscious. The great work of art has come to life.

Up to this point we have been dealing with an extraordinary individual. But how is the subconscious used but normal people, who are not necessarily artists, though able, at least partially, to receive the message and meanings of Great Art? Certainly, in order to receive, “fully understand”, and savour an artistic product, they should put themselves in the position of unaware listening, which is initially not linked to conscious rational schemas and thus dependant on the subconscious. But, unfortunately, the degree of “rapture” is generally lightweight, given poor aptitude for deep-rooted concentration. It also soon gives way quite quickly to total reappearance of the rational mind, which, voluptuously, almost in a spirit of revenge, will compensate for the rarity and weakness of traces left by the great emotional archetypes during “rapture”, by means of an “artificial” recall, from the memorisation areas, of similar archetypes possessed (and identified) and all the relevant modulated dispositional representations (evocation of “states of mind”), re-working everything in accordance with individual cultural levels, which come into play to “mask” true meanings and, often, create the illusion of “true” understanding. Undoubtedly, it is not easy to “feel” a work of art, and it is actually impossible to do so only through the rational mind, seeing that the latter can only get us to “understand” what it wants us to!

Nevertheless, this seems to us, with all consequent difficulties, to be the “mechanism” for bringing art to life, in the creator-receiver relationship.

What part does the subconscious play in everyday life? It is probable that the quality commonly known as “intuition” and which has nothing to do with rational processes, uses the same neural circuit connected to it. Analogously, while the mind’s deductive processes are the result of its rational cognitive activity and its neural circuits, the connected subconscious circuit also probably plays a part in inductive processes.

Finally, what about the physiological substratum of the big bang? We argued that the seat of the subconscious is connected to the cerebellum, which has independent structure and functions in respect of the cerebrum, the seat of the rational mind. It can be hypothesised that, during the activation of the functions linked with deep-rooted concentration, which are necessary for activation of the unconscious function, a direct connection can be set up between the external computational structure of the microtubules activating the subconscious and the “storage” of neural dispositional representations due to emotions, so that the conditions can exist for “a sudden flash of awareness”, with total exclusion of the cerebrum, completely bypassing it. When “everything is ready”, by means of an exchange signal between the external and internal structures of the microtubules, the “large scale quantum coherence” effect (a non computational phenomenon) should be present in them, with the coming to life of the “artistic event”, supposedly immediately fixed in dispositional representations by the neural circuits connected to the areas of the subconscious. Subsequently, on the “reawakening” of sudden awareness, these neural circuits are automatically re-connected to the cerebrum, and the conscious mind acquires perception of it and begin the rationalisation process, extraction and translation into appropriate language also using the specific technologies and methodologies of expression typical of the sector to which the achieved artistic event belongs. It has also been argued that Great Art is only accomplished when there is a passage from a kind of “digital representation” to an “analogical” one. In our view, this is possible if, at the moment of “the sudden flash of awareness” there actually is a change to the “analogical” of the dispositional representations connected to the areas of the subconscious.

What is the difference between an artist and a normal person? The subconscious brain areas possibly connected to the cerebellum, as already mentioned, can be activated, probably only for intuitive, automatic functions. In our view, the artist, apart from an extraordinary, genetic predisposition, has an exceptional aptitude for concentration and meditation, together with a special creative “enthusiasm” conditioning his/her very will, compelling him/her to total dedication to a personal artistic (or scientific) dream. Ability to concentrate becomes so deep-rooted over time that the rapture mechanism is set off, guided by the areas of the subconscious, but also with overall bodily involvement.

12.1 – Different ways of practising art. Grading artistic levels

We have examined the various types of creativity, in accordance with the brain areas affected. They are obviously related to different artistic results. However, it should be recalled that a great work of art is never the result of only one kind of creativity, but rather the harmonious and highly balanced mingling of the three kinds listed above. This does not exclude the possibility that an artist only rarely achieves harmonisation of these components, actually, sometimes through laziness, calculation, or habits acquired later, neglecting deeper meditation, which could lead him/her to the “automatic” synthesis sparked off by the true “big bang”, surrendering to the most convenient component at the moment (usually of the elaborative or re-working rational kind). When this happens, the artist only follows the “academy”, limiting him/herself to “self copying”. But if we are dealing with a great artist, the public will be satisfied nonetheless, because his/her discursive “style”, touch, brilliant rational inventions will hide from the majority the inspirational emotional poverty of his/her work. Picasso the “great artist” is only really “great” in some of his works, characterising his various artistic periods. But, even in his works with no “archetypal creativity”, his drawing, colours and his way of carrying out a rational synthesis, making it appear to be true inspiration, reveal his extraordinary personality.

In the same way, Mozart was not always in top form, because, being such a great joker, often simply provided what he was asked for (conventional music), putting himself to far less psychic effort. But when he wanted to stretch himself to the maximum, he reached the greatest heights, even though this was not that easy in his century, inclined more to re-working fancy and manner than deep-rooted concentration.

So, in our view, analysis of the artistic level reached by a work cannot neglect:

- identification of pure emotional, expanded and composite archetypes present, and, at the same time, analysis of the uniqueness of the overall archetypal expressions evoked, with the purpose of establishing the “absolute” level achieved. Clearly, Great Art requires the sequences of these expressions, normally present in many high quality works, to be realised in a totally original, unambiguous manner, and, typically, for the first time, so as to constitute a true cultural “school” in the present and at the same time “creation of dependence on future cultural directions”;

- identification of mental re-workings of the above mentioned archetypal forms. Here rationality can reach excellent heights, with the creation of rhythms, methodologies and expressive technologies carried out with new, original modalities, which, on occasion, mask the very archetypal form from which they derive;

- identification of autonomous mental elaborations, where emotional archetypes or their re-workings are absent, but which consist of sequences of purely logical, numerical, rhythmic, sign archetypes, among others, which rationality can posit in totally original forms.

As we already said, Great Art certainly should show the signs of “a sudden flash of awareness” which has evoked and “turned into archetypes”, in a unique way, sets of emotional archetypes, and also the signs of extraordinary rational re-working, together with autonomous elaboration, so as to form an exceptional complex, where the three above mentioned components are flanked by original expository and compositional logic, as yet unseen, and difficult to achieve in centuries to come, even though the necessarily derivative “school” will only shed light on these qualities later, attempting to codify them in rational canons. This will favour both the emergence of mannerist disciples and artistic rebels, who, reaching the greatest heights, will repeat the Great Experience in an innovative way.

13.1 – The basic structural language of music and the other arts

Music is said to be the most exhaustive and complex of all the arts. It has more colours and chromatic shades than painting, greater plasticity, concreteness and ability to express reality than sculpture, much greater capacity for analysis and explanation of emotions, psychological situations, individual and collective dramas than literature.

In short, music appears to include, realise and transcend all the other arts; and now we know why. Since the heart of the original emotional archetype is made up of sound and rhythm, it is natural for it to contain the absolute synthesis of human expression and manifest it in musical elaboration.

But how is the latter linked with hearing, the primary organ whose function is that of receiving, comparing and analysing rhythmic and sound expressions? Actually, though some of the archetypes can, before birth, be imprinted internally, by means of elastic waves enveloping and crossing the embryo right from conception, subsequently, after birth, a sensor for their transmission to the nervous and brain system is required. Without hearing, sounds cannot really be picked up and put to use, and hearing should be good for good message transmission quality.

Similarly, it is impossible to paint or appreciate painting without sight, and sight must also be good, since someone who is colour blind certainly does not transmit a good visual message to the brain, at least from the point of view of the individual’s talent for artistic elaboration and evaluation.

Admittedly Beethoven was almost deaf, but he reached this stage when his mind had subjected his brain and nervous system to perception of musical messages which could also come from the sight and analysis of a score rather than from a performance. Thus, on the other hand, at the moment of the big bang carried out by the subconscious, he had all the technological means for memorising it and subsequently writing it down on paper.

These considerations lead us to underline the great importance of individual (efficient) senses, at least during the period of the human mind’s archetypal acquisition. These are admittedly genetically guided, but can only be carried out on condition that they correspond to the sensory organs controlling their subsequent evocation and expression. The problem of re-expression of archetypal forms (especially in their psychological component) had, over time, gradually found ever more satisfactory, exhaustive solutions. After the human voice, artificial instruments were “invented”, for the purpose of re-expressing and “re-listening” to the archetypes involved. Percussion instruments, the primitive flute, and then strings etc. came into being to “re-listen to themselves” and psychologically “mime” the archetypal stylemes, in onomatopoeic forms as well. It can be hypothesised that archetypes deriving from natural sounds (e.g. thunder) can be evoked by man made instruments (such as the tam-tam and tympani). Sound onomatopoeia becomes evident if we connect the sound of breathing and wind to strings, especially violins (psychologically expressing the “breath of the spirit”), the human voice to the ‘cello, the various voices of nature (including those of animals) to wind instruments, and rhythmic and non rhythmic noises (heart, thunder etc.) to percussion. Humans have, as it were, unconsciously re-invented musical instruments because they needed this type of recall, their evocative power to “clothe” their archetypes with sounds of psychological value and listen to them again expressed by means of those technological modalities. Undoubtedly, instruments have their own essence, their own voice from the genial elaboration of the material of which they consist, which will always be different from the “voice” of an archetype springing from the subconscious with mechanisms inside the brain-cerebellum-nervous system complex. However, in order to exist and manifest itself, Art requires material support, in human guise.

To return to music, let us take a look at the relevant structures. Structural “logical analysis” will be required, seeing that identification of the archetypes and their re-workings allows their logical-emotional language to be revealed. From this the basic message of the composition can be reached, though all this must be accompanied by detailed analysis of the expressive technologies used for making the message more original and exact.

In our view musical structures are made up of a basic structure consisting of a complete breathing archetype (or its re-working), within which emotional, numerical, rhythmic and logical archetypes appear.

It should be remembered that the breathing in and out archetype is closely linked to the question-answer logical one and, on occasion, be “constituted” and superimpose itself over it, since it needs “at the same time” to express two or more different mental or emotional contents. Therefore, the piece being analysed must be split up into sequences of breathing in and out archetypes. We must also note whether there is psychological correspondence with question-answer archetypes and then analyse the inner workings of each sequence. We shall normally find the emotional archetypes made up of single (or groups of) notes as described in § 7. 13, with numerical, rhythmic and logical ones at intervals.

Here we must be very careful.

We recall that a) each single note can simply be a numerical or rhythmic archetype (e.g. one of strength) and only psychological correspondence will be able to tell; b) each set of two notes (with stress on the first) at a distance of one (or more) falling (rising) semitones can make up gentleness (bitter) archetypes at different levels; c) each set of more than two rising (falling) notes can make up a rising (falling) archetype, with or without its re-working, with different speed, if the notes are at a distance of a semitone, tone or more than one tone; d) each set of notes “turning back on themselves” can make up a doubt archetype (on very close notes) or a question one, or their re-workings, or “superimposition” (composition).

In Appendix 3 we provide an example of archetypal-psychological analysis. This is the kind of analysis that needs to be carried out on musical scores, in order to begin to understand them.

The following comparison is of special interest. When the first sequences of hieroglyphics were discovered in the tombs of the pharaohs, their link with a precise “language” able to communicate a specific message was not initially obvious, until the discovery of the “Rosetta Stone”, which made translation possible. Each hieroglyphic was made up of signs, colours, and symbols, which, in themselves (as in music), appeared to express “something”. As the centuries passed, the style (but not the essence!) of the representation of each hieroglyphic changed and this was mistaken (as in music) for a change in language, and thus in the message, while it was only a change in the “expressive technology and methodology” of the different concepts.

14.1 – The development of musical elaboration in the archetypal hypothesis

Let us take a brief look at the historical development of musical elaboration.

We know very little of the situation before ancient Greece. Pythagoras was certainly among the first thinkers to posit “associating music with numerical relations innate in the harmony of the Universe”. Plato saw music as the constituent, adjacent, interrelated elements of “harmonia-rhytmos-logos”. Thus the two philosophers foresaw the possible existence of numerical, rhythmic and emotional-rational (logos) archetypes, sustained, in Plato’s view, by the “World of Ideas” (or as we prefer, by “universal memory”). We know little of ancient Roman music and Japanese, Chinese or Indian music are very far from our culture. Even if archetypes are identical over time and space, with only slight differences, re-workings have certainly been different, since there have been different approaches to post-perceptive emotional and logical problems.

Ancient European music really began with Gregorian chant, which found inspiration in the deepest Christian spirituality. Archetypes are thin on the ground; correspondence was perhaps sought between external sonorities outside church walls and sonorities within the soul to be transformed into mystical exaltation.

After the Gregorian period we have the music of the Troubadours, thirteenth and fourteenth century court music. The spirit was not the only musical referent and the first emotional musical archetypes appeared, together with the beginning of musical re-workings recalling amalgamations of material and spiritual realities, while the logical-rational element linking the different musical moments was still extremely simple and basically unstructured.

The “stranglehold” of the mind arrived with Johann Sebastian Bach. Here we have structuring of musical discourse, a search for the logic of musical language (but including certain, though rare, emotional elements) and the codification of harmonic elements in the theoretical development of the tonal system, which finds in the Art of the Fugue one of the milestones of the development of music. For example, the last counterpoint on the name B-A-C-H (the letters corresponding in German to the English keys B flat, A, C, B) adds to the logical structure of the Great Fugue the symbolic elements linked with the composer’s name, among others. If Bach was able to construct a pre-established musical edifice, as it were, nowadays we can do more: with adequate computer software which can identify keys and maintaining chromatic relations, we can reconstruct the logic of the entire quadruple fugue and substitute the four B-A-C-H notes with any other four, obtaining another quadruple fugue. This procedure can be repeated for all the groups of four notes that can be put together from the basic twelve notes, obtaining a number of fugues equal to the simple placing of twelve objects (as we learn from combinatorial analysis) four by four, i.e. 12x11x10x9=11,880 fugues! We might find some more beautiful and significant ones among them as compared to the original, owing to the archetypal stylemes “rediscovered” by logical-computerized means, rather than the composer’s own wishes. This is the kind of “stranglehold” the mind can be for us! It should be pointed out, in any case, that Bach was not entirely hypnotised by the architecture of his own creation. There are external musical features and concepts in almost all of the composer’s fugues, falling like meteors causing harmonic-melodic intrusions which brilliantly redirect the fugue’s “automatic” route. For example, in the Well-tempered Clavier, in Fugue II, 3 (three parts) the exposition of the subject theme is arranged thus: subject-answer-subject overturned. The immediate presence of an overturned subject is really unusual. Again, in Fugue II, 5 (four parts) the anomalies are abundant: the countersubject deriving from the coda of the subject (without monotonous effects, as usual); the countersubject which is not in double counterpoint; the fifths in similar motion, not in inner parts. Yet this is a wonderful fugue clearly expressing the difference between art and craftsmanship.

Moving on from Bach to Mozart, we cross over an abyss in a span of a few years. The period saw the growth of eighteenth century formalism and musical “gallantry”. This had repercussions in the suspension of the process of evocative amplification of emotional archetypes, both in the simplification of Bachian logical musical architecture, and in the creation of musical forms suitable for “background” music (with certain important exceptions such as Handel and Haydn).

The scene changed significantly with Mozart, though he was not indifferent to the Baroque musical fashions of his time. Nevertheless, he broke the rational “stranglehold” created by Bach once and for all and found an emotional “streak” (was his own private licentious life a help here?). All music after him is certainly in his debt and the Requiem, his last composition, at least in its original parts, is a mixture of heart rending pain mixed with the highest hope, almost as if awareness of a new beginning grew out of realization of the end. Mozart is arguably the founder of the true romantic ideal.

Romanticism claimed the right to irrationalism, a kind of powerful resurgence of emotional archetypes which had been kept under control for too long. Here we have Schubert and Beethoven: poetry and Hegel’s ideal in the context of an entirely personal conception dominated by an ethos, a group will be represented by the individual genius.

It was only Brahms (preceded to a certain extent by Schumann) who reached the fulfilment of the vibrations of the individual soul. The pure and expanded emotional archetypes are evoked in re-elaborative syntheses containing all the affective subtleties. Brahms is a universal love act embracing every instant in life from a unique poetic standpoint. He associates all feelings, even vigorous, tragic ones, with an intimate drama, whose key can only be discovered if one follows, with great humility, paths, sometimes crooked and tiring, sometimes straight, which he himself points out.

The National Schools were a follow up to Brahms. The vibrations from the souls of specific ethnic groups reached their peak. States of mind and ways of feeling common to a specific ethnic group were sought and identified. It was a heady period of liberation, long suppressed new energies completed their search for a common destiny and models of accepted group identification. These new emotions are communicated by the great composers of the National Schools in their music, trying to identify, associate and express the relevant groups of archetypes with modalities and methodologies totally characteristic of the ethnic group to which they refer. The National Schools of France, Spain, Russia, Norway, Finland, Bohemia, N. America etc. bear witness to the great evocative pathos achieved and perhaps still to be surpassed.

Then, immediately after the National Schools, and after Mahler, Strauss and Berlioz – heralded by Wagner, Franck and Fauré, we have the Impressionists, then the Expressionists, as a negative reaction to an over codified musical language characterised by chromatic excess and as a return to the Romantic individual, almost rapturous relationship with an artistic object. Even the tonal system broke down, with the introduction of a new scale, in which semitones are abolished, with decisive consequences for harmony and great novelties in the field of the technologies of musical expression aiming at the construction and elaboration of special “atmospheres”, though the archetypes do not change.

At the same time Shostakovich was being forced by Marxist ideology to identify the vibrations of the collective soul, in conflict with his desire to preserve, at least partially, his originality.

Answers came from Bartok and Stravinsky. But atonalism and dodecaphony in a search for new aesthetic-musical canons are on their way. Abstract music comes to the fore, where the pure archetype, almost without logical, structural interventions or mental, or cultural backwash is directly projected into the work of art.

At this point, there follow Stockhausen and electronic music and “multimedial” music and so on…the adventure is still in progress.

14.2 – Consequences for musicology

Archetype theory also has some interesting consequences for musicology. Some musicologists (Dalhaus and Eggebrecht 1985) have been tempted into thinking that different “musics” in different times and places exist instead of just “music”. This is clearly the deduction of anyone who does not acknowledge a single musical language as the basis of all music and the existence of a single “cerebral modality” presiding over the formation of any artistic expression. Let us think for a moment of the absurdity of conceiving various pictorial, sculptural and literary phenomena as separate entities, practically due to individual whim or accidental necessity, rather than originating in the insuppressible human urge to perceive mysteriously, understand consciously and, in the end, express Great Art as a moment in the ongoing psychic evolution towards assimilation and self-conscious identification with nature (prefigured and expressed in the world of ideas and in universal memory).

Returning to music, it is true that for some centuries, the scientifically codified tonal system was believed to be interchangeable with music itself, since it had definitively united and expressed musical language. But when it was realized that art could be created atonally and electronically, it became clear that either a new unifying factor had to be found or one would have to turn the singular “music” into “musics”. Admittedly ethnic and cultural diversity has given rise to different formative principles that need to be accepted. However, the possibility of analyzing, understanding and comparing them only lies in the hypothesis of the existence of a sole basic archetypal language, even though it can be supplemented by autonomous mental re-workings and elaborations almost chromosomally recalling “self-supporting” differences among human groups. Archetypal articulation allows the formation of purely musical concepts and, subsequently, thoughts. Their correlation with rational concepts and thoughts is only possible archetypally and never contextually. It should also be noted that more than one musical concept can arise from the same pure, expanded or composite archetype. These concepts have the same essence but differ in the different “affinities” of archetypal components within the musical thought elaborated and developed by the composer.

An example of correlation between rational and musical thought is to be found in vocal music. We see the human voice as a double operator, used simultaneously either for the enunciation of a musical theme, like an instrument, or for carrying on rational thought. Therefore, the same archetypes give rise, at the same time, to both musical and rational discourse. It is, however, the “text” which (obviously) comments on the music, since there need not be any need for a literary “translation” of a musical text to understand it, even though this is possible.

Nobody wants to undervalue the worth and greatness of opera, which can attain excellent expressive and artistic heights (and this is what happened in 19th. and early 20th. century Italy), but also with the help of non-musical means. We do not only mean the “sung text”, which is a means of expressing rational literary concepts and emotions, but especially the techniques of stage expression. Pure music requires none of this.

We mentioned non-musical means. Here we are still in the face of ambiguity, with hair-splitting musicologists trying to distinguish the “purely musical” from the “non-musical” with the intention of separating “true” music from “interference”. Nevertheless, in the most serious European musicological tradition, from the 19th. century onwards, “purely musical” means “purely instrumental”, the human voice only being accepted if used as an “instrument”. In the same way, a non-musical element arrived with “programme” music. Much was made of unacceptable pollution and corruption first of the composer and then of the audience. And yet no one can deny the importance of some of the symphonic poems by Rimsky-Korsakov, Dvorak and Strauss etc.; “programme” music par excellence.

Later, for many musicologists, the idea of the non-musical was extended to all “interference” which could condition music and distance it from what is “purely musical”.

Even the character and cultural make up of composers and the inspiration deriving from the context in which they lived were challenged. There is food for thought in the fact that even Beethoven’s music has been seen as “polluted” and described as full of “non-musical” elements since “it bursts out from a state of tension imposed by the will”, so that his work is “shifted from the purely musical and aesthetic sphere to the ethical and moral one” (Handschin 1948).

In our view, the conflict between the “purely musical” and the “non-musical” is once again due to the fact that music was analyzed starting from music itself and not from human beings. We believe that the “purely musical” is only an attribute of an archetype and perhaps of its mental re-workings. We see the conflict between “musical” and “non-musical” as only being resolved by the archetypal hypothesis, which leads the artistic element back to a common root, so that ALL music (like all artistic expressions) can be seen as of the “programme” type (the programme consisting of the sequence of archetypes), while, at the same time, NO music is of the “programme” type (since any pre-established intellectual draft can only be musically, or in the other arts, expressed by means of archetypes).

Furthermore, there is no sense in talking about coincidence between the “purely musical” and “purely instrumental”, since each instrument was made artificially by humans so as to express and “mime” their archetypes, and this is already something “non-musical”. In this respect there is no difference between a violin and the cannon used by Tchaikovsky in the place of timpani in the 1812 Overture.

To return to Beethoven and his presumed “non-musical” character due to his “fault” of deriving his superficially defined “purely musical activity” from his ethical-moral conceptions (i.e. “programme” music), our view is that there is nothing more comic, unscientific or further from the truth. It is our opinion that ethical components and moral impulses, and the state of tension imposed by the will, are the elements, appearing in the composer’s spirit where the “continuous, deep-rooted meditation” took place and determined the conscious and unconscious evocation and subsequently the choice and use of archetypes which lead to “purely musical” discourse and thoughts, such as those Beethoven expressed. Certainly, we acknowledge that the great ideals which inspired Beethoven and which he projected so sharply and vigorously, will always be present (like a kind of canon) in all his works and will determine their greatness, but also mark their limits. Humanity lies behind those great ideals. Its mysterious intimacy, which Beethoven could perhaps not perceive, was only to be revealed for the first time, as we have already remarked, with Brahms.

Our view is that musicology, often crossing the borderline with musical philosophy and practised mostly by scholars with great literary talents from musical conservatoires and musicology graduate schools (following on from arts degree courses), should change direction and become a science at last, making use of all the relevant resources and methods. Certainly, if Music is the synthesis-Art, the basis of human knowledge (the “intimate essence of the world” in the words of Schopenhauer (1896)), it requires scholars able to analyze it with the tools of science (mathematics, physics, bio-physics, neurology etc) well beyond mere analysis of expressive methods, as has been the case so far.

15.1 – Nature and art. The world of ideas (and universal memory) as sources of emotional archetypes.

The materialist and spiritualist hypotheses on the reality of human beings.

Considerations on human ability to express the mystery of Art, and thus of Music, would risk being interrupted at the half way stage, if we were not to make some reference and formulate hypotheses on its genesis and reality in nature. The general framework needs to be put together, in order to endow the vast evolutionary process of which we are protagonists with meaning.

The first consideration that immediately comes into view is acknowledgment that Art is not an abstraction of Nature, our “mental invention” aiming at imagining and representing our capacity to approach aesthetic perfection, but, by means of “supplemented archetypes” (which are actually “granules of concentrated Art”), enters each of us as a basic component of all our emotions, thus being an intimate part of nature, of our nature. Why then aren’t we all “artists”?

The reason is that, in order to spark off the artistic recall by means of the big bang, deep-rooted meditation is required on what we would like to express, accompanied by cultural gifts, specific determination, concentration etc., which are not part of everybody’s make up. These qualities are acquired by a long rational-mental and “physical” process, bringing about the required cognitive skills, methodologies, technologies and means of expression. Nevertheless, all of us, to a greater or lesser extent, can “recognise” true Art by means of our archetypes. It should also be pointed out that the definition of “Art” should be extended to the whole field of what can be known and expressed, where extraordinarily original results can be attained. The “trigger” is, however, always the same: concentration followed by the unconscious big bang.

A further essential consideration concerns the need to investigate scientifically our way of being, our very existence in relation to what appears to be outside us, but may not be.

We will attempt to base what we are going to say on scientific grounds, admitting, when necessary, that some hypotheses are not yet backed up by scientific findings. We will also point out fideistic hypotheses used to illustrate various current philosophical-religious conceptions. Unfortunately science is in its initial stage with regard to human conscious and unconscious perception and the required relations with “what can be perceived”. If our non computational archetypal acquisitions are, as we believe, of a psychological nature, what “external reality” does our psyche communicate with?

The real world, our “universe”, the space and time in which we live all seem to lie at the origin of our perceptions, which reach us “clothed in matter” and strike us, remaining permanently imprinted, but among them there are those that cause us to “vibrate”, implying “emotional feeling” and which endow us with “consciousness of feeling emotions”.

Let us try to list the aspects of reality that appear to be necessary for explanation of the complexity of the human psyche, which we have conceived as having a conscious and unconscious mind, with qualities for acquisition and containment of the computational, non computational, structural and emotional.

Were real ideas already present at the birth of our universe (the physical big bang) and life? We believe that this is the case and that the basis of everything is a “Universal Container” supplied with a “memory” (called the “World of Ideas” by Plato), holding the original emotional Archetypes, but also the logic required for their continuous re-working and use.

We have seen that archetypes have “skeletons” of the logical-mathematical type. This leads us to suppose that “pure mathematical forms” make up the “heart” of the World of Ideas. This “world of pure mathematical forms” was reflected in our “physical space and time” conceptually structuring the Universe we live in and placing itself at the base of its “physical laws”, at the same time taking charge, during the course of human evolution, of the “rational construction and structuring” of our minds (Penrose 1994: 452-458) (operational formation of the brain neo cortex), by means of the continuous, successive “metabolisation” of the gradually imprinted emotional archetypes, from which the mind itself drew the logical, numerical and structural archetypes.

The mystery of rational “understanding” of mathematical laws, which only begins at a particular point in evolution (i.e. the appearance of homo sapiens), as well as the discovery of the laws basic to the physical world where we originated, proves that the “world of pure mathematical forms” existed before both the physical big bang and the formation of life. It is difficult to imagine that, immediately after the physical big bang, spherical shaped material formations, circular shaped particle trajectories etc. appeared without the general hypothesis that the π mathematical form-idea (the constant supporting these realities) did not exist before their appearance. The same is true for the e neper number or the universal gravitational constant etc. It has often happened that, in the advance of science, general logical-mathematical properties (pure forms) have come to the fore during theoretical elaboration of physical hypotheses. This kind of elaboration is impossible without this type of general structuring. These properties already existed and were unpredictably hidden until an already structured rational mind (i.e. that of a scientist) found them and made them generally available. Certainly, as has already been noted, the “mathematical laws of physics” we derive from our rational mental qualities do not always perfectly coincide with physical laws. We still do not know whether this is due to our mental limitations in rational reconstruction of mathematical forms, or whether it is a characteristic of our Universe tied up with the principle of its “irreversibility”, which is now being seen as basic by scientists (Prigogyne 1953) for explanation of certain presumed “discontinuities”. It is highly probable, as already mentioned, that this is due to the lack of a physical-mathematical theory introducing the “non computational” as a basic feature and which is able to describe “irreversibility”.

Admitting that pre-existing “pure mathematical forms” are situated at the heart of the world of ideas, we have seen that they can be of the computational (rationalisable) and non computational (intuitable by consciousness) type. However, emotions (or “emotional archetypes”), being structured both computationally and non computationally by pure mathematical forms, must already be present before the perceptive mental moment. We could actually say that they are “emotional ideas” that become “emotions” when perceived by a living being, and then that every idea can only be perceived by the psyche if it becomes emotion.

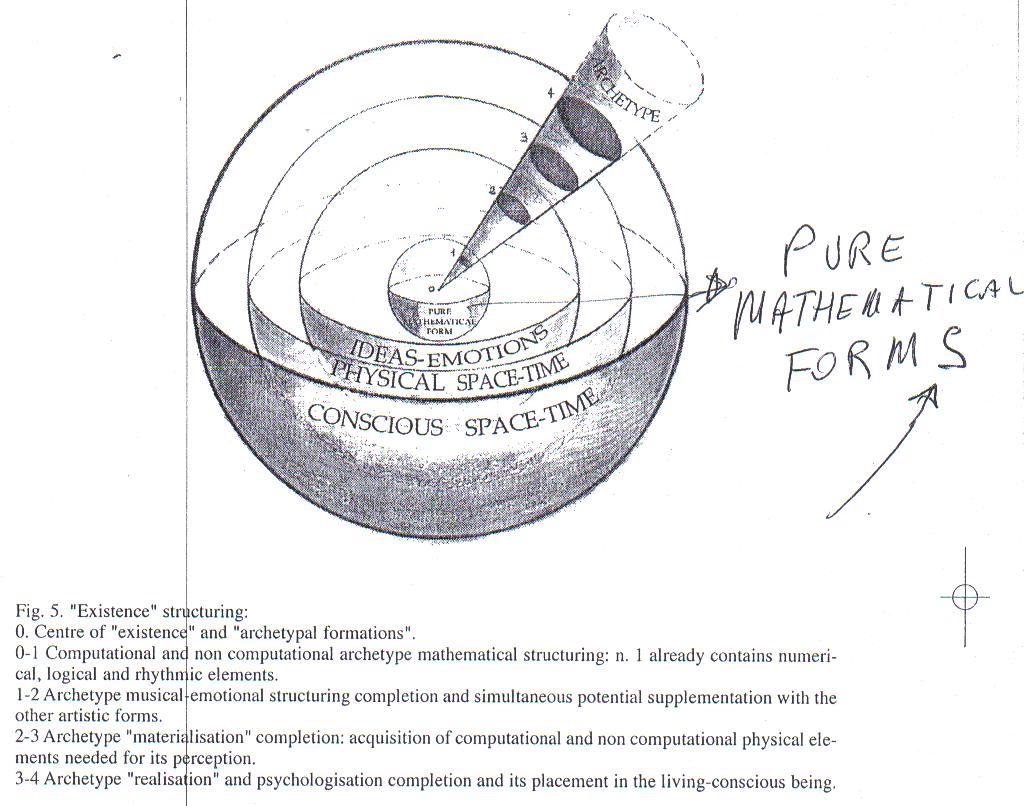

Thus the existence complex (Penrose 1994: 500-504) could be structured as follows: an ideal spherical representation and propagation (see fig. 5) with the “pure mathematical forms” sphere nearer to the centre, then, concentrically, the “ideas-emotions” sphere, and finally the non living “physical space-time” and “conscious space-time” spheres (we, as living beings, belonging to the latter, as the last stage in the evolutionary process). It should be noted that each “sphere” is presumably actualised starting from the common centre and, from the outset, takes part in archetypal structuring.

We could thus conceive of the present psychic heritage of humanity as being made up of a set of archetypes subject to subsequent, continuous implementation. Pre-existing mathematical-structural archetypes were gradually endowed with logical and rhythmic elements, followed by emotional and musical ones, at the same time being supplemented by other artistic-natural qualities (§ 7.11), subsequently being “clothed” in matter and life. So our psyche could only be the local, partial, actualised reflection in living space and time of a pre-existing Universal Psyche containing the original emotional archetypes, which were then “realised” in us.

In our view, all the above rightly belongs to science, not science fiction. However, science needs to broaden its horizons, including the non computational “structurally” in overall scientific theories. Even a scientist like Roger Penrose (1994: 472-476) accepts the need for science to take this radical step, so as to escape from the exclusively rational-computational “ghetto” and “stranglehold” from which it appears to be suffering, predicting the advent of a hitherto unknown type of physics (described by non computational mathematical forms) covering classic and quantum levels and thoroughly explaining the workings of biological systems (such as our brains) which appear to make use of it. Modern philosophy of science is clearly in difficulty (Dalla Chiara and Toraldo di Francia 1999) over enclosing the laws of quantum physics in a rational paradigm. The latter are “reluctant” to face any attempt at logicalisation making use of classic procedures. We may be heading in the direction of simultaneously valid logical plurality, a characteristic of the non computational.

While waiting for science to develop in this direction, what have philosophy and religion had to say on the subject?

The substantial difference consists in the ethical-moral approach, in the overall tendency to identify behavioural codes in humans and nature. Philosophy tries to analyse every situation in which the stream of emotional-rational sequences is to be rationally controlled on the basis of general rules of coexistence and organisation (problems of knowledge, ethics, political philosophies, philosophy of law, economic doctrines, sociology) or of artistic expression (aesthetics). Religion, on the other hand, moves emphasis onto the moral problem, the existence of the “absolute” ideas of “Good” or “Evil”, which in the so-called “revealed” religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) becomes a dogma to be accepted with faith, together with sets of rules to follow, which are necessary for achieving the goals of each religion. In other religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, theosophical cults etc.) the ideas of Good and Evil are seen as “relative” or complementing each other, in accordance with individual levels, so that “evil” is only a “lesser good”, and is a necessary step for the continuous evolution of the individual in the direction growing spirituality. But what characterises all religions (and generally distinguishes them from philosophy) is the idea of God, i.e. of a “spiritual” and especially immortal Creator.

This idea is basic to the fideist dispute between materialists and spiritualists.

For the pure materialist the human psyche is mortal and undergoes the same process of decay as the physical body. The “Universal Psyche” we hypothesised only really exists as long as a human psyche does, and it ends with the latter’s end.

For the spiritualist God coincides with the “Universal Psyche”, considered immortal like that of each individual, which is thought as belonging to another “universe” and not to our space and time, where it operates through the mediation of the physical body.

The essential characteristic of human incarnation supposedly consists in reproducing (and regaining) the ideas and emotions in humans which previously existed in the Universal Psyche. The spiritualist distinguishes, in the psychic field, the “spirit” (taking its “essence” in the world from “Pure Mathematical Forms” and “Ideas”) and the “soul” (taking its essence in the world from “Ideas and Emotions”). The human psyche thus made up (i.e. Spirit+Soul) supposedly has its own independent life separate from the body holding it, with the possibility of projection and “materialisation” autonomously and independently from the physical body, even in our space and time.

Naturally experts and other scholars must retain, unless proved otherwise, his/her “scientific doubt” (even towards science itself!) and can only consider materialist and spiritualist “faiths” convenient standpoints, without being at all conditioned when formulating philosophical or scientific theories or interpreting experiments, even though he/she may (inevitably?) express personal preferences for either conviction.

16.1 – Conclusions

Nature as mimesis of Art: this is the view of Plato, who believed that ideas absolutely precede any sensory manifestation of them and are infinitely more complete and perfect. When an artists copies (or mimes) nature, he/she is doing something wrong and insignificant i.e. making a copy of a copy.

This view, which we would call “aesthetic excess”, lacks awareness that it is only by means of sensory manifestations that we can be conscious of and recognise the existence of ideas, which, otherwise, would be unknown to us and thus of no use. As far as the artist is concerned, one thing is “computationally copying reality” and another is surrender (by means of the subconscious) to a “violent blow”, the big bang straight from emotional archetypes, which are something like the “quanta” of the world of Ideas. Probably, only “self-conscious science” (Leroi-Gurman 1982), only new physical theories based on non computational mathematics and able to thoroughly describe the irreversible nature of space and time originating from complexity phenomena (Miller 1975) presiding over numerous non-living manifestations (physical big bang, phase transition phenomena, spontaneous interruptions of symmetry etc.) and living ones (from inanimate to living matter, from the living to the conscious living in its different degrees, to “organisation” phenomena etc.), only the definitive abandonment of the “stranglehold” of the computational mind, which has become something of a “scientific prejudice”, will allow an interpretative forecast of the state of our reality.

For the moment, we must go beyond the “stranglehold” with the help of non computational ideas/emotions. It is here that the contribution of Music is decisive, seeing that its “sphere” is essentially one of “mediation” and is a link between the sphere of pure mathematical forms and that of ideas/emotions. Musical archetypes are the structural basis and pure language of the conscious mind and, in our view, are the only possibility for (genetically guided) re-acquisitions of human intellectual qualities from conception onwards.