6.1 – The mechanism of communication – message and artistic language

Webern stated that human beings could only exist at the moment in which they expressed themselves and that music expressed itself in the form of musical thoughts. Obviously a work of the highest artistic level is a point of exceptional human “expressive density” for us. Every artist expresses a specific “message” which must be communicated and understood by means of a specific “language” made up of perceptive/emotional phonemes and re-elaborations by means of (rational) mental expressions. However, expression and understanding of the artistic message can only lie in the fact of possession of identical “emotional granules” (which we shall call emotional “archetypes”) both by sender and receiver. If this were not the case, communication would be impossible. Mental re-elaborations are undoubtedly influenced by the structural complexity of individual minds, with which an individual cultural make-up is linked. This can influence the degree of understanding of these re-elaborated expressions, seeing that individual cultural levels vary with personal development.

We said that human beings live inasmuch as they express themselves in their inter-relations. In normal circumstances, for communication with others, a message is set up using rationalised mental re-elaborations of “emotional granules” (re-elaborations mostly consisting of the use, as we shall see, of the structural, logical and numerical archetypes present in them) contained in neuronal dispositional representations in the nervous system that can be freely called upon. When humans create art, a message is also intended, usually consisting of “rationalised emotional content”.

Each artistic field, though, has its own unavoidable “technologies and methodologies of expression”. For example, in painting the message is stamped on the work of art by signs and colours making up its expressive language. These signs, which can be coloured, consist of the various depicted forms and their attitudes. If, for example, I want to communicate a message of strength, gentleness, or languid sadness etc., my language will be made up of male, female or landscape forms depicted so as to foreground these different attitudes, and the situation will not change if the forms become abstract. Obviously, depiction is achieved by means characteristic of different artists, such as drawing, line, brush strokes, colour alignment etc. These are “technologies of expression” and are not to be mistaken for the artist’s “message”, which consists of transmission of a mental or emotional sensation issuing from the “deep-rooted vision” preceding the artistic act. The great work of art undoubtedly consists of an extraordinary “message” activated by means of “refined” technologies perfectly adapted to an extraordinary occasion and which have reached their expressive peak. Evaluation will include analysis both of the deep emotional and re-elaborated parts in the light of the quality of the activated expressive technologies. In the same way, with sculpture, the message contained in the work is not to be confused with the expressive technologies consisting of the plastic, spatial “mode” in which the work is created that is typical of the artist.

With literature the question is less complex. The message is contained in the concepts expressed, which reflect and explain the artist’s emotional content and mental re-elaborations. This is not usually confused with expressive modes (or technologies) chosen. For example, in poetry, we can choose the sonnet or ode form, decide whether to use rhyme or not, or whether to use onomatopoeic words to reinforce the concepts. Nevertheless, all of this is not to be confused with the “message”.

In dance the message is easily perceived, and the expressive technologies aim at bringing to the fore the rhythmic schemes (which, as we shall see, can also become sources of emotion) expressed by body movements. There is a similar situation in individual and team sports, as the (physical-aesthetic) art of human body movement.

This brings us to music. Here things are much more complicated, and we shall see later why. Nevertheless, there is certainly emotional-rational content (i.e. a message) here too. But it is so well hidden, so disguised as to lead many astray in their attempts to decipher it. Most musicians (and, sadly, musicologists) have constantly mistaken “message” for the “technology” employed to express it. Now, the “expressive technologies and methodologies” of music consist of musical notation, the harmonic-melodic construct, rhythm, timbre (with the various instrumental voices), dynamics, structuring music through the various expressive forms (sonata and concertante forms, ballad, dance, triumphal or funeral march, hymn, song etc.). But all this should not be confused with the “message” (even less so its “language”), which is expressed by use of the above mentioned expressive technologies and methodologies to display its main concepts more exhaustively. So what is the musical message and what is the nature of its language?

We insist on the fact that the message consists of acquisition and communication of a deep rooted “overall emotional sensation” (translated into a “musical thought” which displays itself as modulated, coloured, interwoven with various emotions during a musical performance), and that – as we shall see in the next section – can only be expressed by means of the language of archetypes (i.e. by means of the flow of “granules” containing, in embryo, the essence of the message itself). Once the composer’s mind has “become conscious” of emotional sensation (which reached him/her – in our view – from the subconscious), these “granules” can only be rationalised and presented by means of the above mentioned expressive technologies and methodologies, which, by conferring formal structure on this language, amplify, complete and render it unique and original. They can also change over time, depending on the period and ways of feeling and expression. But, as already mentioned, above all, they cannot be mistaken either for the message or language, as has often been the case up to the present (Harrer and Harrer 1977, Ferrari and Bramanti 1988, Ratalino 1997).

Now, so that the musical message can be transmitted by the composer to the receiver their emotional “granules” require the same set up and the acquired archetypes need to be identical. These are communicated to the consciousness of the artist, performer and listener by the series of musical notes representing them which the composer placed in a logical sequence choosing and using the required expressive technologies and methodologies, so as to set up “concepts” which together realise the “musical discourse” contained in the score. Only thus can the “discourse” be turned into “musical thought”, be understood, supply unique mental, emotional and physical sensations and become an object of “culture”.

Naturally, we must point out that the message in musical thought is made up of musical concepts and discourses that are much more than a mere sum of the archetypes used and that emerge from their inter-relations, from the syntactic and semantic role, often only hinted at, as well from the overall harmonic context in which they are expressed and which force the musicologist to carry out an exhaustive analysis of all the features of the message.

7.1 – Sensory-emotional archetypes, emotions and their memorisation

The creation of “emotions” in a living being is due to computational and non computational sensory stimuli caused by inner or outer events reaching and penetrating him/her involving various organs. A simple outer environmental event, such as a sound or flash of light, or an inner event (a heart beat) cause electro-chemical events in receiving organs (ear, eye etc.) reaching the central nervous system (the primary sensitive cortices) setting off, for a specific time span, retroactive, “resonance” oscillation (§ 3.1, § 3.4) which activates the innate and/or modifiable neural circuits, creating, in a developing brain (of a newly born baby), a stable system of elementary mnemonic storage (stratified sensory archetype storage) with a specific mechanism (probably Edelman’s guided synaptogenesis, with the formation of dispositional representations by means of tubulin dipoles etc.). These “elementary sensory perceptions”, when newly occurring in a more adult brain (in which the self-conscious phase has already begun), cause cognitive elaboration, beginning from their comparison with similar perceptions previously placed in mnemonic storage and reaching subsequent, immediate realisation association with a “context” (or contextualisation) and their interpretation. This last process, which is often very rapid, leads to what we call “elementary emotion”, or rather, to the creation of an emotional “archetype” or “granule”, which is also placed in an emotional archetype storage system.

The recording mechanism of emotional perceptions thus consists of the ability of the brain and whole nervous system to favour the setting up of permanent dispositional representations by means of innate or modifiable neural circuit activation. Naturally, true “emotions” (made up of series of emotional archetypes) are “interpretations”, or “elaborations of contextualised sensory stimuli”. Consequently, emotional mnemonic storage is set up, ontogenetically, after that of both sensory and emotional archetypes. Besides, different dispositional representations resulting from the same emotional event realised by circuits connected to the various receivers belonging to the organism can interconnect through synapses, realising their emotional contextualisation and then the creation of emotional storage that will allow subsequent recall complex emotions simultaneously concerning different organs. This is not the whole picture. We have also seen that the general arrangement of the dispositional representations of the same emotion can be shaped and enriched over time (and be newly stored), when emotions of the same type reach a human being at further stages.

Now, the nervous system of the human embryo is structured under genetic guidance, from the moment of conception, over a few months, covering the whole of evolution: first the perceptive-emotional acquisition and memorisation organs and then the rational ones. Thus, the individual’s nervous system, though having all the potentialities required for emotional and rational acquisition right from birth, must, as it were, “learn again” how to use them, and this happens as of the first sensory-emotional perceptions.

So, if we wish to analyse the receptive mechanisms, we shall have to direct our attention to the first sensations reaching the human being both during formation in the mother’s womb (probably after the third month of life) and after birth. We shall call these primary emotional perceptions “original emotional archetypes”, since the language of the mind in embryo is based on them, before their metabolisation and analysis mechanism comes to the fore, leading to the structuring and re-acquisition of the rational abilities of the mind. We prefer the term “archetype” to “imprinting”, in view of the recognised genetic predisposition for acquisition of these emotions, as well as the different origin of this predisposition, hypothesised by several philosophical and religious schools of thought.

7.2 – The archetype formation mechanism

The phenomenon we call “archetype” is formed and fixed in the neuro-cellular brain structures prepared for the formation of the “mind’s deep memory” (which, as we have seen, is situated in mnemonic storage receiving permanent dispositional representations due to innate neural circuits), when an “original stimulus” presents itself for the first time on its nervous ends, sent by the senses which collected it on the outside (or inside) of the human embryo. By “original” stimulus we mean a sequence of waves (formed by electrical potential variations propagated along the neuronic structures, with a contribution from the electro-chemical mediators) derived from “drives” connected with the organs carrying out the human being’s main innate functions (vital, survival and reproductive ones etc.). These drives, which generate the above mentioned sequence, are able to collect and transmit by retroaction an exceptional feature of these organs: that of contributing to “generating or perceiving emotion”. For example, the heart, piloted by autonomous neural centres, performs the primary, vital function of blood circulation, but, at the same time, its beat is emotionally “a synonym of life” and the conscious or unconscious mind, archetypally “listening” to its own heart (by means of the same centres and connected neural circuits able to elaborate dispositional representations), perceives and memorises whether it is beating normally, contributing to the generation of a state of calm, or the reception from outside of anxiety, fear etc., when beating rapidly.

Nevertheless, the initial perceived “drives” are due to elastic waves (sounds), seeing that the embryo is placed in a liquid only capable of transmitting that type of signal. Perhaps the liquid is not entirely without “luminosity” (electro-magnetic waves), but it appears not to be “emotionally” connected with the embryo up to its birth.

As already mentioned, the innate neural circuits preside over functions of the body organs common to all human beings, such as those listed above. But, at the same time, these organs, precisely due to their function, can become “emotional subjects” and generate original stimuli, which, still collected (by retroaction) by the innate neural circuits from which they derive, bring about the installation of new permanent dispositional representations, this time able to store and then provoke a “primary emotion”.

We insist on the fact that by “original archetype” we mean something brought to life by “primitive sensations” (or “primary emotions”) due, as we said, to agents within the human body in embryo or outside it, and able to induce in its brain (newly formed or developing) subsequent neural circuit modifications able to provoke permanent dispositional representations (which will together constitute so-called “deep memory”), and this will take place by means of continuous “re-adjustment”. Actually, seeing that “primitive sensations” (or archetypes) being gradually recorded will interact to the point of “fixing” the subsequent ones by modalities and configurations recalling their predecessors, the dispositional representation caused by the last stimulus must be conceived as being due to a re-elaboration and re-connection of the representations induced by previous stimuli in the neural structures of deep memory. We also recall that there could be innate, prenatal and postnatal dispositional representations.

It should be borne in mind that the original archetype set-up is almost completed before the completion of the “critical brain mass” able to set off the phenomenon of consciousness by means of the effect of large scale quantum coherence in the microtubules of the neuronic cytoskeletons. The neural structures are probably already able to operate memorisation.

However, these structures, after implant of the first archetypes, will memorise the subsequent ones, no longer independently but with respect to those already imprinted, through their “filter”. The mechanism is activated by groups of archetypes and is accomplished by synaptic connection of the dispositional representations previously acquired with those due to new sensations, also bearing in mind the ability of the synapses to elaborate “stronger” or “weaker” connections. As we have seen, the nervous system is built up in such a way as to newly “evoke” and recall single archetypes or groups of them formed during subsequent acquisitions, and this evocation can reach the “conscious” areas of the mind (consciousness) as well as the subconscious. It should be borne in mind that the original archetypes participate, together with the other sensory perceptions from the outside, in the build up of a fulfilled “emotion”, which will be memorised. For example, among the first emotions perceived and “reconstructed” by human beings after birth are those related to one’s own “concept of identity” and to the “interpretation” of the world we live in, as appearing through the mediation of parents, who can transmit sensations and emotions of safety, danger, or fear in accordance with their “interpretation” of reality.

7.3 – Deferred archetype acquisition

How long can archetype acquisition last? From the age of three onwards? While this acquisition is incomplete, how does the memory of normal events in life, carried out by cerebral sectors certainly different from those recorded by archetypes, act? Separate moments are probably imprinted (on dispositional representations due to modifiable neural circuits), which are not yet connected by mental structures of numerability, judgement, logic, and emotional comparison, and it is perhaps for this reason that memories of early infancy seem more particular, almost different for each individual, and they become more logical (and emotional) when the main archetypes have been acquired. We have spoken of “primitive impressions”. To clarify the concept we should say that the principal archetypes have always been identical for each individual, since the human brain has allowed acquisition, but the acquisition modality is not always the same.

Might a distorted or insufficient “presentation” of the archetype, which must be fixed and modify the characteristics of the entire capacity for acquisition of deep memory determine a difference between individuals in future chances for logical-emotional control and coordination of all the perceptions memorised? In any case the period of archetype acquisition is a very delicate moment in a human being’s entire developmental phase.

Original acquired archetypes are then analysed and “metabolised” by the mind, seeing that they will subsequently make up the basis for thought. Firstly the logical-computational component is extracted (and “memorised” in special dispositional representations belonging to learning centres) and it is on this that re-acquisition of mental formation and structuring will depend. Immediately afterwards, when structuring has been acquired, the mind will begin to perceive mental images due to archetype recall mechanisms and their emotional modulations. These images, organised selectively in logical sequences (mental re-workings) and translated into an adequate language become “thought”.

Can an accomplished mental re-working be “made into an archetype” and become itself a “set of permanent dispositional representations”? We do not know, but it cannot be set aside. An archetype that appears to be structured by others is actually a single structure, but can “share” elements of other archetypes (such as the numerical, logical, sound-rhythmic or visual ones). In any case it preserves its uniqueness, like a numerical set which is superimposed on or shares in other sets by means of the same elements, though remaining absolutely “unambiguously defined”. It remains to be seen how distinct archetypes can be called and “who” they respond to. But, as we have seen, through the neural networks and circuits of the brain which allow “distinct superimposition” of stimuli recorded or still to be recorded, it should not be difficult to hypothesise and establish the distinct links and spatial-temporal hierarchies, necessary for the methodological logic of a “call” or “evocation”.

7.4 – Differentiated archetype acquisition

Archetype acquisition in humans certainly begins with the sensory archetypes. “Growing acquisition of sensoriality” and its use for the construction of emotions is the proof of this. Nowadays it is common to use the term “emotional intelligence” (Golemann 1996). Therefore, as we have seen, mental rationality begins to build up on emotions, which, from early childhood, our senses allow us to possess and feel. Only afterwards do we have pure intelligence, philosophy, science etc. as mental abstractions of emotional intelligence. We could say that the numerical, logical archetypes etc. are like “archetyped abstractions” which the emotional archetypes can extract, and this appears to be a perfectly reasonable and probable assumption.

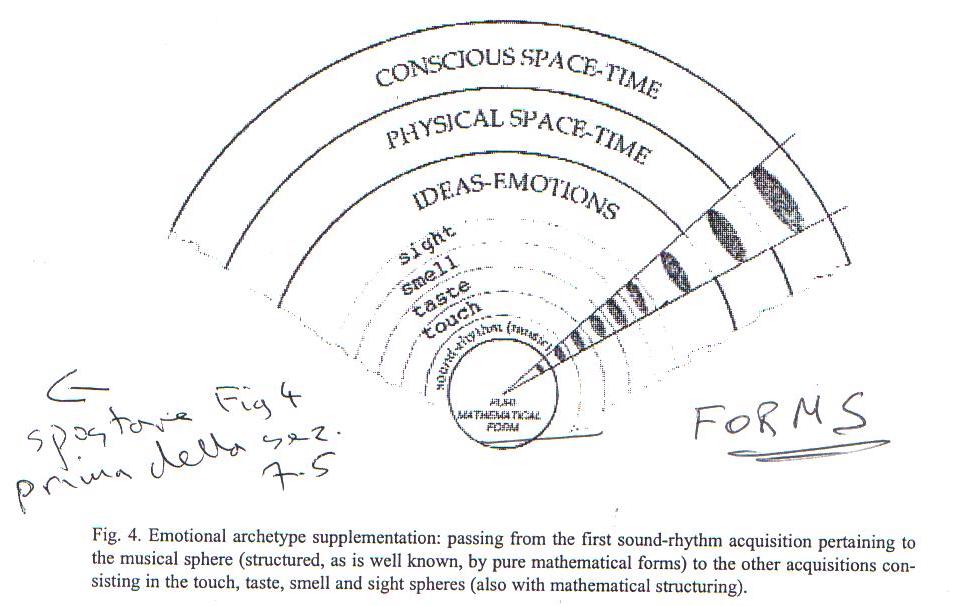

How does supplementation of an archetype take place? In our view according to “growing sensoriality” of the brain acquiring, building itself up with the neural mechanisms already noted, following genetic patterns from the moment of the initial brain cellular formations onwards: once the basic logical-mathematical potentialities have been re-acquired, first the exchange of elastic waves (sound-music), and then touch, then smell, then taste and finally sight.

According to this conception, we would have a “spherical concentric” acquisition and configuration of each archetype. At the centre of the musical sphere we have logical-mathematical abstractions and then the other acquisitions by concentric spheres (fig. 4), in this order: touch, taste, smell, sight). The conception expressed here is a convenient reference, for expressing the set of dispositional representations, deriving from neural circuits spread through the human nervous system, which gradually interconnect by means of synapses.

Actually, we have an original, significant developmental feature: primitive man began to express himself “artistically” from the outermost archetypal sphere, sight (cave painting), to go on to taste and smell (offering his female companion food and flowers in an ever more complex fashion, after going on to pottery (statuettes of gods and then statues-stelae) and lastly sound (Pan’s pipe), almost as though the automatic call upon the archetypes by the original mind allowed their return and re-use starting from “original sensations” acquired last of all. In modern human beings this is translated into growing difficulty in understanding and rational expression of artistic vision, as the innermost archetypal sphere is reached for. This is why music has always been difficult to decipher and always the source of interpretative ambiguity.

7.5 – The exclusively musical aspect of the original archetype

If the “primary emotions” acquired by the foetus before birth are elastic waves, the archetypes deriving from them are certainly “musical”, i.e. they must be equipped with rhythmic a sound structuring. Naturally, the conscious and unconscious mind must already contain a mechanism for perception, not only of the elastic-sound feature, but also of the rhythmic one, i.e. of its spatial-temporal structure. In other words, the “simple” sensory archetype must become an “archetype undergoing a process of internal self observation”, so that memorisation of the characteristics (including flexible ones) linked with its “specific perception time” can take place.

That the first perceived “primary emotions” are of the elastic-rhythmic-sound type is basic to the entire thesis presented in this book. This is why we shall begin with analysis of the rhythmic-sound (“musical”) archetypes, followed by extension to other fields of action, as the other senses (touch, smell, taste and sight) are acquired.

In our view, the (rhythmic-sound) “musical” structure of the archetypes is the foundation, the “innermost sphere” or skeleton of the whole archetypal set up. To identify its manifestation we referred to characteristic sounds, both of the basic functions of the developing or newly born human organism, and of external primary emotions received. Both must have rhythmic-sound characteristics which will lead to formation, in its nervous system neural circuits, of permanent dispositional representations normally coming to the fore both in the individual expressions of the newly born child and, subsequently, in major artistic, musical expressions. Identification of these archetypes will take place with the aid of the psychological component induced by them when acquired and found in the human mind by scientists. Any real emotional situation requires “scientific psychologisation”, seeing that archetypes can only emerge from close scrutiny by scientific psychologisation. It is the task of musical psychologists to complete archetypal listing and identification. Within the limitations of this study it is enough to foreground a possible (and very probable) formation and use mechanism of musical (and, more generally, artistic) language correcting old conceptions and ambiguities, restoring artistic events to expressive unity.

7.6 – Sensory-emotional-musical archetype typology

We shall now attempt to describe the archetypes we believe are situated in the dispositional representations making up original mental memory. Our aim is to identify their “musical” manifestation, with the proviso that this research is in its early stages and needs to be carried on with the necessary scientific rigour by experts in the field.

Firstly, the “sensory-emotional” archetypes require definition. For example, the first physical pain (but also the first caress or first tickling sensation) certainly generate a sensation that will remain imprinted and will open up the way to other sensations of pain, bliss, joy, hilarity, in the soul a swell as the body. Thus we have “frames of mind” as mental re-workings of the “sensory-emotional” archetypes” in connection with the places of memorised modulation of linked dispositional representations (the feeling memorisation areas). Now let us examine the musical aspect of the sensory-emotional archetypes. As already mentioned, the possibility of reception of their spatial-temporal structuring must already be present in mnemonic archetype storage.

Let us begin by analysing the rhythm of the heartbeat, which includes number, sound and rhythm. It is a structured archetype, though still “one” basic archetype, picked up by the embryonal mind at the moment of the first beat of a tiny heart. The rhythm of heartbeats also concerns the “calm” archetype (in normal conditions made up of more than one heartbeat), and the “anxiety” archetype (a speeded up heartbeat due to fear or anxiety). Breathing, after birth, is also turned into an archetype, in its variability and “exchange” modalities with the exterior, with double structuring (breathing in and out).

Peristaltic intestinal movements, linked with digestion, rapid assimilation, and physical growth will contribute to the formation of the “energy” archetype.

The same is also true of the new born baby’s first (rhythm-sound-sense) whimper, which can contain both “sobbing” and “steady weeping”.

The first song heard, such as a lullaby (Zolla 1996), or the first bell probably enter the archetypal sphere.

As they arrive, the five senses determine sound, touch, taste, smell and light archetypes.

Height and depth archetypes come with the first contact with the sense of gravity, perhaps from the first glance at the sky or down an abyss. The “ascent” and “descent” archetypes are associated with them. They are crucial for music, since they are closely related to rising and falling musical phrases.

When someone’s or something’s “prolonged fall” with the associated feeling of impotence is first seen, the “unavoidability” archetype is imprinted in the mind.

The “gentleness” archetype is determined by the first sweet tones of a mother’s voice and the first caress.

The first fright due to a prolonged scream causes the “terror” archetype.

The first emotional reaction to terror causes the “strength” archetype.

7.7 – Numerical, rhythmic, logical, sign and colour structural archetypes

Let us now analyse what we term “structural archetypes” (which, in our view, derive from rational, subsequently archetypal “metabolisation” of sensory-emotional archetypes) since they have an essential function in the logic of all mental (and also musical) discourse. They lie behind the structure of any styleme and elementary phrase, and often mental re-workings are none other than “expansions” of structural archetypes. It should be pointed out, however, that every other archetype seems to have the possibility of being “broken up” into emotional, logical, numerical and onomatopoeic features, among others. Actually, this is not the case. Single archetypes cannot be broken up into elements, just as a drop of water breaking up into other drops cannot be considered “structured” by those other drops. The fact that the developing human brain at the outset acquires logical-mathematical “structural” capacities genetically, as we see it, is no indication of the possibility of regaining and expressing these capacities without a large number of emotional archetypes obeying it being imprinted. We believe that it is only possible to regain and perhaps “make them archetypal” after their rational “metabolisation”. Likewise, the universe, as we shall see, follows logical-mathematical structural laws, but they can only be brought to light and known because it has subsequently undergone physical structuring.

The fundamental archetype in this structural category is of the “number” or “numerability” type: I = 1; I and my mother = 2 and so on. The numerical archetype should be seen as “acquisition of quantitative abstraction”. It may be due to the perception “of a lot different things” reaching a baby in the early months, compared with itself being “only one thing”. The numerical archetype is imprinted as a “unit” and, only subsequently, with the development of logical-computational faculties, can it join the formation of mathematical operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). In music, the numerical archetype comes into the picture, for example, when, in a rhythmic, though uniform manner, one wishes to “mark” a piece (or passage) of music, or, above all, join two phrases originating in pure emotional archetypes by means of rational reworking making use of it. However, it is from the numerical archetype that a true rhythmic archetype derives through reworking, as can be heard in musical “backgrounds” or in performances of individual parts by percussion instruments (drums, timpani etc.).

Curiosity as a vital stimulus and emotion may lead to the first logical or “question” and its associate “answer” archetypes. Could there be a correlation between the question-answer composite (or re-worked?) and breathing (in and out) archetypes? It seems clear that the breathing archetype, made up of two parts (breathing in and out) is the first “logical” element in the mind’s deep rooted memory. The objection could be made that a heart beat is also made up of systole and diastole, but its structure is fixed and the duration of each part cannot be deliberately modified, unlike the first elementary manifestations of mental logic. Subsequently, when a child suddenly acquires self-consciousness and is able to “reply” to vocal stimulation (even his/her own name), the question-answer archetype is fixed and will gradually add all the logical attributes as the development of mental re-elaborations proceeds. Question-answer archetype acquisition probably takes place by means of a breathing (in and out) archetype supplementation mechanism.

The doubt archetype may well originate in the first “uncertainty” in life (the child’s first uncertain steps?). The associated musical response is a brief sequence of notes “turning back on themselves” and at a distance of a semi-tone, or at most a tone (this depends, in a psychological interpretation, on the need “to lean on what is nearest” in moments of doubt).

The “question” and “doubt” archetypes are structurally very similar, though a difference does lie in the fact that the notes “turning back on themselves” can be at a distance of two or more tones (in accordance with the greater or lesser degree of “doubt” in the question).

The “impassibility”, “continuity” or “waiting” archetype, probably a single prolonged note, not in the background but clearly audible, albeit at the same time as others, has no “rhythm”, the phrase is interrupted, and, for its duration, everything is crystallised in “everlasting breathing in”.

The “sign” and “colour” archetypes due to visual abstraction of possibly coloured images will be analysed in the section devoted to visual perception.

We could also hypothesise a “silence archetype” which should coincide with the “absence of archetype” archetype.

7.8 – Onomatopoeic and behavioural archetypes

We also have “onomatopoeic” archetypes imprinted in the mind by human and natural situations. These are connected with music that “imitates” nature (thunder, horses hooves, marches, trumpet calls etc.).

As the mind develops, re-workings of behaviour archetypes can be imprinted, such as a sense of duty and the first “rules” to follow. Logic of actions and situations develops, which music takes up as discoursal features inserting sensory-emotional archetype re-workings, though they be difficult to separate from these re-workings. Again, it should be pointed out that further research and an exhaustive list of archetypes are needed.

7.9 – Rhythmic-tempo archetype analysis

Do archetypes have their own tempo? Seeing that they can be represented by musical stylemes, often made up of several notes, can performance tempo be varied without distorting them?

It should be immediately made clear that each individual, when receiving his/her archetypes, always activates different modalities, so that it can be argued that archetypes differ from one individual to another. But how different are they? The answer is immediately forthcoming. Their diversity must not prevent recognition. Each individual must be able to recognise another’s archetypes as if they were his/her own. This means that the musical tempo scanning the archetypal styleme must not vary more or less than 10-15% of each individual’s normal value. In this range we are sure that recognition can take place. In the end it is nature that comes to our aid. Humans can “recognise” their fellows, as long as the differences are not too great.

For example, physical traits (height, outer dimensions of organs such as the mouth, nose, ears etc., distances between organs such as eyes, ears etc.) cannot be larger than their specified sizes. Our genetic heritage ensures that individuals cannot normally be born with eyes at a distance of five or thirty centimetres. The same must be true for archetypal stylemes. So, since a musical composition is a sequence of archetypal forms and their re-workings, there is a “basic” interpretation (clearly specified by composers, who usually supply a “metronomic tempo”) which cannot be too varied. This makes conductors respect metronomic tempos and limits their interpretative freedom. It is a question of applying interpretative criteria, where this can be done, without altering archetypal language. For example, the greater or lesser length of pauses, varying degrees of distance between separate passages to be linked “ad libitum”, “crescendo”, “diminuendo”, “fortissimo” and “pianissimo” markings are all things the conductor can decide on.

But the speed of a whole (or part of) a tempo must follow the composer’s directions, or, in their absence, the basic archetypal styleme. For example, if this is “sobbing” the “proper” tempo is well known. The tempo cannot be “doubled” without distorting the very meaning of the music. The interpreter does not only have the possibility of varying the tempo of a whole musical phrase, but within it, can vary the proper tempo, and consequent rhythm of the archetypal styleme, making it difficult to recognise and assimilate for the listener. For example, a “quicker” reading, a more “rapid” archetype rhythm “compresses” the archetypal stylemes and their re-workings, a consequent loss of definition of the whole musical message, while a “slower” reading and rhythm results in “upsetting” the stylemes i.e. the features of musical thought, producing consequent loss of synthesis and thus difficulty in understanding.

A number of university research projects on the possibility of unambiguously establishing the rhythmic-tempo interpretation and performance of basic archetypes by means of information and communication theory are of particular interest. As is well known, during “communication” the signals emitted by sound (or other) sources are received after passing through a means of propagation. The process can be described as a “source-channel-receiver” with the “channel” having all the qualities of the means by which propagation takes place, such as attenuation, distortion, systematic or chance disturbance etc. of the (sound or electro-magnetic) signal produced by the source.

In communication studies the theories of Wiener (1948) and Shannon (1948), with their mathematical formulations, are applied. They supply the characteristics of the received signal (as a function of the channel produced alterations) and give sufficiently exact information on its difference from the initially emitted signal. To obtain this it is necessary to place a “codifier” between the source and channel, and, analogously, a “de-codifier” between the channel and receiver. The function of these tools is to “adapt” the emitted and received signals to the transmission channel. Sometimes the signal needs to be turned into “digital number sequences”, which are more suitable than analogical signals for treatment (including that of the probabilistic type) of the information contained in them (Fano 19610).

How should these theories be used for the study of archetype “distortion”? The answer is simple: We substitute the “source-channel-receiver sequence with that of the “composer-orchestra-listener”, noting that the composer is the “source” of “non-distorted” music which can be identified by a totally faithful reading of the musical score and/or by specific notations in it (metronome tempi, psychological or performance notes which must find objective counterparts in the typology of archetypes used etc.), while the orchestra (with its conductor) is, actually, the “channel” allowing the listener (or “receiver”) reception of the music, introducing (or not) differences (“distortions”) in respect of an absolutely faithful reading.

Mathematical formulations (G. Tacconi, personal communication) of communication theory allow identification and quantification of differences in respect of originary archetypal forms, by identifying “a specific performing tempo” of the archetype within the limits of “psychological” understanding of the archetype itself. They also allow judgement of whether listening can actually permit exact perception of these forms (even though with some understandable approximation, due to the conductor’s “interpretation”) or whether the distortion introduced creates irreparable psychological fractures preventing understanding owing to a loss of definition or synthesis of the message. Research is still in progress but of considerable interest.

7.10 – Archetype identification

Identification of archetypal stylemes in the brain receptive system, in the shape of dispositional representations, should not be a difficult task for modern neurophysiology, especially if the stylemes being looked for are those due to innate neural circuits. It is a question of carrying out a cerebral analysis on a subject with an electro-encephalograph connected to an NMR apparatus capable of measuring his/her reaction to deep stimuli, and subject him/her, under specialist controlled methodology, to a basic neutral stimulation with, at intervals, a series of sound and/or light stimuli, made up of impulses representing a chosen archetypal styleme (for example, the sobbing archetype: tà-tatà-tatà-tatà) with its own rhythm and tempo. The styleme sequences will need to be slightly varied to find the typical one for the individual subject. This is followed by measuring of the intensity of individual reaction both in basic stimulus conditions and to the various styleme sequences. We should be able to find archetypes from the wave shape in resonance conditions, corresponding to wave peaks. Analysis may need to be carried out under hypnosis or a light anaesthetic, so as to interrupt the conscious, rational circuits that could “mask” the archetype or prevent it from coming to the fore. Special care must be taken with what stimuli the subject receives, seeing that we must separate the “response” given in the presence of an archetype from responses to superficial “peripheral” sensory stimuli. Subsequently, if a resonance response is determined, the subject needs to be given the same deep stimuli musically “mimed” i.e. reproduced by different musical instruments. If the archetype is universal, we should have the same response, whatever instruments have been used, seeing that an archetype is being looked for. Research should continue with comparison of results on a series of subjects, so as to see if wave peaks have “variations” in rhythm and tempo in the chosen archetype for each individual. Variations should not exceed 10-15%, as seems to be suggested by communication theory.

7.11 – Supplementation and universality of archetypes

Another very important subject is the “universality” of archetypes, which must be able to affect each sense ready to express it. This is an essential condition for various artistic expressions (painting, sculpture, literature, music etc.) bursting forth. We have mentioned the fact that the same archetype, once acquired by rhythmic-sound (“musical”) means, is “supplemented” or “expanded” by acquisitions of the same type, though originating in other senses. Besides, it could be that this process does not only take place by means of other archetypal acquisitions, but also by mental re-workings which are “added” to the initial archetype. As we have already stated, the universal archetype “supplemented” in this way should not be considered as “having structure deriving from the sum of the various archetypes”, but is actually realised by a set (configuration) of synapses controlling permanent dispositional representations (including those acquired later).

The definition “supplemented” or “expanded” refers to the temporal modalities of acquisition. Let us provide an example. The gentleness archetype, acquired by a newly born baby, initially through a sound: tàa, is supplemented by the stimuli from a caress, and then from a very gentle look and maybe from the mother’s scent. This “supplement” to the archetype certainly takes place at different times, and is due to formation of dispositional representations from innate neural circuits linked with the various sensory organs of reception, which is subsequently (once supplementation has been completed, preferably according to pre-established genetic schemas) “definitively transformed into an archetype” so that the previous incomplete archetype actually ceases to exist, even though it will be neurally possible to recall individual expressions of the archetype (which will later become the protagonists of various branches of the arts).

The expression of an archetype in a work of art needs to be “technologically activated” according to the type of art involved. If it is painting, the gentleness archetype can develop in the contents (e.g. a representation of a man or woman looking at an object of his/her love with gentle intensity) and then a mental reworking will be needed to create a scenario and protagonists. It can develop in the expressive form with direct reference to the archetype (e.g. very light brushstrokes, with very close colours, almost to the point of integration – a kind of chromatic onomatopoeia of the musical archetype); or in both modes simultaneously. If it is sculpture the gentleness archetype can develop either following figurative contents or through extremely soft surfaces or with high continuity, or with both modalities. With literature, whether it is poetry or not, the gentleness archetype is made manifest through both conceptual contents and the “right style” to express them.

7.12 – Expanded and composite archetypes

In artistic expression, especially musical compositions, stylemes which cannot be traced back to a single archetype are often to be found. Though they are certainly complete in themselves, they are “integrated” by other original archetypal forms, almost as though they derived from the “fusion” of two or more archetypes. We called them “composite archetypes”. Furthermore, there are stylemes with varied forms of an archetype and we do not know whether they are mental re-workings subsequently “turned into archetypes” created by the conscious rational mind or produced solely by the subconscious. We called these “expanded archetypes”. We shall now attempt to provide examples and analyse them in detail when taking a closer look at the differences between the functions of the conscious mind and those of the subconscious during the manifestation of a work of art. The importance of the “association” of several archetypes (bearing in mind what was said in § 7.3) or of their “expansion”, and the possibility of these “associations”, together with their rational re-workings will clearly come out when we analyse the formation mechanism of Great Art, which consists in a “unique” composition at the subconscious level of sets of associated expanded archetypes and their re-workings which have become archetypes. Great artistic expression (whether it be musical, pictorial, or of another kind) can thus be made up of a single archetypal element (or only a few of them).

7.13 – Archetype listing and musical analysis

We shall now list the main archetypes found and analyse musically. We shall attempt to define them by means of sound-rhythmic stylemes, and, when possible, by musical notation with examples collected together in Appendix 1.

It should be recalled that the musical notation used for the sound-rhythmic stylemes is not all embracing, but can have different configurations in accordance the chosen tempo for performance of the musical phrase containing them. The stylemes, as already mentioned, can or may not be identified with true archetypes (or their re-workings) and this will be shown both by their placing in the musical context (which must take on precise meanings because of their presence) and by analysis of the psychological correspondence of the musical context. Furthermore, it often happens that different archetypes joined together or following on from each other are to be found in musical phrases, and it is not always easy to isolate them one by one from their stylemes.

The breathing archetype is perhaps the most difficult to identify. Its sound corresponds approximately to the aa-aa-ae-ee (breathing in) and ee-ee-ea-aa (breathing out) styleme. Musical translation, considering the variability controlled by breathing, is extremely difficult. There is no clear duration, seeing that breathing can be ample, drawn out, but also short and panting. Its duration then can cover an entire musical phrase or just a few bars. It is generally made up of two parts (the same logic as question-answer), but partial uses can be expected (psychologically, simple breathing in=”life and waiting”; simple breathing out=conclusion and death). Musically speaking, reference is often made to “long (or short) breathing” phrases, almost with unaware reference to the archetype.

The heartbeat can give rise to the calm archetype, if the heart is beating normally (ta-tà, ta-tà, ta-tà styleme) or the anxiety (or fear) archetype, if the heart is beating quickly (tattà-tattà-tattà styleme).

Crying gives us the sobbing (tà-tatà-tatà styleme) and steady weeping (taàa-taàa styleme) archetypes. For a new born baby crying is nearly always a physiological need. We shall see shortly its psychological counterpart in the adult.

First seeing somebody’s or something’s “prolonged fall”, accompanied by a feeling of impotence for modifying what is happening, impresses the inescapability archetype (tata-tàa or tatata-tàa styleme) in the mind. The first two (or three) notes are equal, though re-workings with different notes can be introduced to vary or dilute the message. It is up to the composer’s “genius” to clothe the archetype with appropriate notes and place it in a harmonic context characterising the specific situation.

The first gentle call from a mother, almost a whispered caress, made up of two falling, one of which differs by a semitone, generates the gentleness (or tenderness) archetype (tàa styleme), which will soon be in turn emitted by the new born baby. As the two descending notes are separated by more than a semi-tone, gentleness diminishes, becoming a demand for something. The re-workings of this archetype will be analysed shortly.

The first fright, due to a drawn out scream, generates the terror archetype (taaàa styleme).

Reaction to this fright generates the strength archetype (ttàa, ttàa styleme), subsequently supplemented by onomatopoeic features.

Logical-mathematical mental re-working generates the numerical archetypes from the original emotional ones. Musical translation of the numerical archetype consists of a rhythmic styleme coupled with sequences of notes. We can identify the unitary (I = 1; ta styleme), binary (I and my mother = 2; tàta styleme), triple (I and others = 3; tàtata styleme) and quadruple (tàtatata styleme) archetypes etc.

“Height” and “depth” emotional archetypes give rise to the “ascent” and “descent” logical ones (psychologically to exorcise and control emotion by rational mechanisms), whose musical translation consists of scales of ascending and descending notes. Here one can hypothesise a different “speed” in ascent or descent given by the distance of the notes in the ascending or descending scales: a semi-tone, tone more than a tone etc. This “speed” should not be mistaken with the quicker or slower tempi of their musical performance. Groups of ascending or descending notes arranged in “jumps” can take the place of whole scales, as can also be the case with musical phrases containing fragments of scales alternating with groups of notes arranged in “jumps”. The logical doubt archetype arises from emotion caused by uncertainty: in its musical translation a brief sequence of notes “turning back on themselves” at a distance of a semi-tone (or at the most a tone) (ta-ti-ta styleme).

When curiosity joins uncertainty the “question” archetype is created. Its structure is very similar to the doubt one, from which it more or less distinctly differs when the notes “turning back on themselves” are at a distance of more than one tone (almost as though curiosity has overcome uncertainty). But is the question archetype a true one or an “expansion” of the doubt archetype, or even a mental re-working?

In music we often have a “question” archetype immediately followed by a sequence of notes logically expressing an “answer”. Do they make up a single composite “question-answer” archetype? Usually the group (or two groups) of notes “turning back on themselves” end on a note equal to the initial one. In any case, the question, almost always containing elements of doubt, will be expressed musically by means of notes at a distance of a semi-tone (a tone at the most), while the answer, if it is doubtful or evasive, will analogously see notes at a distance of a tone or semi-tone. Otherwise, for a certain answer, the notes could even be at a distance of two, three or more tones (psychologically, less necessity – or even refusal – of the adjacent one).

There is an interesting parallel with Greek metre: the gentleness archetype is in the trochee or dactyl (re-working); the calm archetype in the spondee, the anxiety one in the iambus, repeated several times, the solemn strength (re-working) and inescapability ones in the anapaest.

8.1 – The stranglehold of the rational mind

A newly born child, up to at least the age of six months, “continuously gives off archetypes” (especially perceptive-musical ones). After learning them, even partially configured and embrionally re-worked, it emits them with the available means (mostly vocally), before starting out on re-acquisition of definitive conscious mental rational structuring, due to plot construction and systematic assimilation of reality (Restak 1988) imposed by its parents and the environment which is necessary for the creation of a “relational” language, by means of which it will learn inter-personal communication. The child does not need the subconscious (as the adult does) to retrace its archetypes emotionally. It probably does not even need connection with the unconscious function, which, in our view, develops and subsequently is made manifest, almost as a reaction to the imposed conscious mental structuring. Initially, a brain “learns” by rhythmic-musical scansions, which become its “absolute language”. This is reflected in differentiated languages on all knowledge. During this process as we mentioned, mental rational structuring takes place whose foundation is the structural, rhythmic, numerical and logical archetype set up “extracted” by the sensory-emotional archetypes and used in all mental activity. These archetypes are well known to the mind, which uses them automatically in its normal activity. The conscious mind can (Blakemore 1988), with the already noted mechanisms for mental image recall, be the rational seat of emotions due to re-workings of sensory-emotional archetypes, but these must be subservient, in their conscious expression, to the now acquired structural modalities of the mind, which conditions their re-appearance by re-working them logically and imprisons all their explosive potential in rational convolutions. In our view, it is this that constitutes the so-called “stranglehold of the rational mind”. It will permanently prevent the human being practising his/her normal rational activities from freely and automatically re-expressing emotional archetypes, which will “come to the fore again” complete and originally joined, only during “genuine artistic expressions”, the “sudden inspiration” (we call “big-bang”), probably with the decisive contribution of the subconscious. The common rational language (and very often the articulated musical phrase), albeit of a significant expressive degree and of great cultural value, only contains mental re-workings of these archetypes. It also appears clear that, before learning rational language, the child needs to learn the “language” of the archetypal complex. No exact name (such as that carried out by words and concepts) can be given to mental and emotional sensations without their being already in the form of an archetype, even though it is embrionally re-worked. Certainly, the habit of giving names to the various aspects of reality and using normal spoken language for communicating ideas and feelings will bring about permanent stratification, as already mentioned, probably in memory storage of the rational re-workings of the archetypes, which, in our view, prevent direct transmission of “deep-rooted emotional messages”. This is only possible by means of the artistic “big bang”, with the intervention of the subconscious. The procedure described is closely adhered to by neural circuits for the realisation of the various dispositional representations. Those containing the structural (numerical, logical etc.) information extracted from the sensory-emotional archetypes to be used by the rational mind have been fixed in memory storage after realisation of the dispositional representations directly caused by sensory-emotional acquisitions and their “metabolisation”. They are now a kind of “screen” for them and the recall or re-evocation that, in the form of mental images, the brain can make of them by means of strong or weak synapses.

Interesting observations can be made of the stranglehold of the mind in autistic children. Many of them have seriously communication difficulties. They are still incapable of using language at the age of three, and yet some of them at this very age have exceptional drawing abilities, in a few lines being able to pin down whole emotionally rich well drawn events. However, when, at the age of nine or ten, they go to special schools and learn to use logical reasoning and at last begin to speak, they lose their former drawing ability and revert to that of normal children, which is of relatively poor quality. Evidently the archetypes whose evocation was easy, pleasant and automatic with automatic participation of the unconscious functions are “blocked”, as soon the screen function of the rational mind is activated.

But what actually recalls the archetypes? Consciousness, the mind-nervous system complex, the subconscious, independently or connected together? Can this be done simply by using the by-pass circuits? Have all the recall systems and their modalities been listed and identified in neurophysiology? When are the neural network systems capable of differentiating, receiving and selecting the various archetypes and their re-workings, if they are fixed in deep rooted memory storage, structured and in working order in the human nervous system? At the moment there is no easy answer to this question, though hypotheses to be examined later have been posited.

8.2 Mental re-workings and autonomous elaborations

Pascal wrote that the heart has reasoning that the mind cannot understand. He was the first to have the intuition of an unbridgeable gap between the emotional and rational states. The aware, self-conscious individual has a rational mind able to recall emotions from the dispositional representation “store” and perceive what the subconscious, stimulated by deep concentration, returns. However, it should be recalled that, for the rational mind, emotion “in itself” is absolutely “incomprehensible”. The rational structure of the mind originated in its “metabolisation”, but it is now something of a prisoner and can do nothing but review – though without actually understanding them – memories of emotions and try to reconstruct them in its own way. Once the rational mind has acquired structural capacities and the possibility of applying them to reality by means of the formation of mental images mirroring it, it can proceed with re-workings of these images due to the stored original archetypes as well as autonomous “technical” elaborations of numerical and logical archetypes, which we will subsequently find linked to the formation of speech and basic concepts for human communication, but can in no way experience an “emotion” it does not understand and which cannot be rationalised (non computational), even though it has taken the logical-structural life blood from it. When a mind wishes to communicate an emotional state to others reality does nothing more than recall the re-workings of the emotional archetypes it finds in the dispositional representations deposited in its memory and try to find an echo of similar re-workings in others and thus exchange something like a common vibration. During an artistic act the mind can only “order”, or bestow logic (language) on the succession of archetypes evoked by the subconscious and transmit the message “unawares”. Both originator and receiver initially only perceive or re-work language, but cannot possess its message unless it posits itself in a state of “unaware listening”, where the rational mind is finally reduced to silence and the tools of deep rooted concentration, intuition and the subconscious are put to use. The main activity of the rational mind is re-working. Now, as has already been mentioned, our view is that mental re-workings and autonomous elaborations are a “stratification” of dispositional representations separating the “deep-rooted” memory storage area (the seat of the dispositional representations due to pure emotional archetypes) from that of “normal” memory storage (the seat of the dispositional representations due to imprinting of the events of life on the modifiable neural circuits). If this be true, in music, archetypal re-workings and the technical mental ones belong to this stratification, so that musical (or generally artistic) realisation can be made up of pure composite or expanded archetypes (originating in deep-rooted memory through the subconscious), rational re-workings or autonomous elaborations carried out in specific mental locations, and it will be possible to reach analysis and classification of the artistic level of a composition (see § 12.1) in accordance with the density of these three components.

8.3 – Examples of mental archetype re-workings

We said that the “gentleness archetype” is defined by the first vocal caress heard as “tàa”, two notes, of which the first is stressed, at a distance of a descending semi-tone. This sound is also emitted by the mother addressing her child, who emits it in turn variously modulated. Mental re-working of the initial leads to gentleness that can become less intense, i.e. gradually “more bitter”, if the notes are at a distance of more than a semi-tone (from the 1st level to the 12th – octave). The child actually in turn emits sounds of this type when it wants to attract attention at all costs. Each interval of descending notes should be analysed and related to the musical phrases containing it, so as to grasp its psychological aspect exactly and identify its meaning (see Appendix 1).

However, the true “bitterness” or “hardness” archetype (though we are not sure whether it is an archetype or re-working), emitted and re-acquired during an “effort” or difficulty is defined, unlike the gentleness archetype, by two notes at a distance of an rising semitone and its mental re-working (expressing the rising interval of two notes at a distance of more than a semitone), as the interval increases, expresses the growth of bitterness (from the Ist to XII – octave), which becomes hardness, physical pain, anger, fear and also terror (which we autonomously defined an archetype, but which could be roughly represented by configurations of this type). We give an interesting example in Appendix 2-a of a composition making use of numerous hardness archetypes (Dvorak, “New World” Symphony – beginning of 4th movement).

Even during human sexual intercourse groans, cries and modulated sounds can be heard, which, when the expression of sensations of delight, exactly mime the gentleness archetype in its “sweetest” structure (the two sounds are at a distance of a falling semitone), which can gradually become more “bitter” following the “progress” of the intercourse, while, when the climax is reached and subsequently the mental re-workings of the bitterness archetype can be heard in a strong crescendo, the sign of a “bitter” pleasure reaching the threshold of pain.

To return to the gentleness archetype, it can be placed in a musical context made up of minor keys, thus becoming “sad” gentleness. If the context is mostly in a major key, gentleness becomes “calm”, even “joyful”. If the context is atonal or electronic (using a synthesizer), then, so as to differentiate the two kinds of “gentleness”, different (real or synthesized) musical instruments are used, as well as onomatopoeic methodologies.

The gentleness archetype can be “expanded” to tenderness by means of onomatopoeia with the bodily movements characterising it (tàatàa styleme – see Appendix 1) and tenderness can become gentler or more “bitter” as the archetype it derives from moves further from the first level. As usual, the musical context will reveal whether the tenderness is sad or calm.

Similarly, regarding the sobbing and steady weeping archetypes, for a new born baby crying may simply be a physiological need, without further implications, at least in the early stages but with the adult it is caused by deep rooted emotions associated with pain or sadness.

In the latter case, probably by means of mental reworking it can become a (re-worked or expanded?) sadness archetype (tàatatàa styleme), a bearer of generalized sadness, and, by re-workings musically including the harmonic intervention of minor keys and necessary chromatic passages, can fill a musical thought. Naturally, crying can be caused by pain, but also by anger or joy. These sensations will be communicated exactly by re-workings and, especially, the harmonic-musical context.

The weeping archetype usually consists of the same note repeated three times, the second and third possibly differing by a semi-tone, or, at most, a tone (cf. the different embrional or re-worked (?) kinds of crying of a few months’ old baby).

An example of the sobbing archetype can be heard in Grieg, Peer Gynt, 2nd. theme from Solvejg’s Song (Appendix 2-b), while the re-worked sadness one can be heard in Beethoven, 3rd. Symphony (Eroica), 2nd movement-Funeral March, where the reworking contributes solemn sadness, or in Chopin’s 2nd piano sonata in B flat (Funeral March), where the re-working contributes great intimacy (Appendix 2-c). An interesting example of the “expanded” sadness archetype can be found in Dvorak, Slavonic Dance n. 10 in E flat (Appendix 2-d). The inescapability archetype (and its splendid re-workings) is to be found in Beethoven, 5th. Symphony, beginning and most of the first movement (Appendix 2-e). The strength archetype is often re-worked onomatopoeically with adequate musical instruments, which can highlight solemn religious gravity or non-religious triumph, examples being Brahms, 4th. Symphony (beginning of 2nd. movement) or Handel, Music for the Royal Fireworks (beginning) (in the latter case) (Appendix 2-f).

We should point out that musical notation used by different composers to reproduce archetypes are extremely variable, according to tempi used (two or four fourths, three or six octaves etc.) and the speed of single movements due to metronome markings in the score. What does not vary is the archetype’s rhythmic-sound structure and tempo (apart from small expansions or reductions which have no influence on its perception). This explains some obvious differences between our standard representation of archetypes in Appendix 1 and those in Appendix 2.

8.4 – Examples of logical archetype re-workings

We said that the first element of logic is present in the breathing archetype, which seems to anticipate the logic of the question-answer archetype. A large number of musical compositions contain re-workings of this archetype (and this is quite natural, seeing that the rational mind, almost automatically – even willingly – carries out re-workings that are perfectly adequate for its structure). Undoubtedly, for precise understanding of the type and motivation of the question, and, if required, the answer, psychological analysis is always needed of the reason why the composer made use of this archetype. Some examples (see Appendix 2 and 3): Bach, Toccata and Fugue in D minor (beginning), Dvorak (Uccelli 1997), Cello Concerto in B minor (beginning of 1st movement).

8.5 – An example of archetype integration: visual perception

When passing on to examination of archetype “supplementation” and integration modalities by different sensory perceptions from the sound-musical ones (which, in our view, are subsequently acquired) it may be of interest to analyse hypotheses and experiments on the outset of visual perception and the main theories concerning it.

When examining cave paintings dating back more than 30,000 years our attention is attracted by vertical signs and curved lines representing animals and, occasionally, scenes from daily life. It is thought that these messages had communicative functions between primitive humans, before the development of adequate verbal language for naming the animals and describing the scenes. Precise images were unnecessary. Simple signs in a rough context were enough to recall an animal of fact for primitive consciousness. Hubel and Wiesel (1981 Nobel Prize winners) (Hubel 1966, Ramachandran 1988, Gregory 1966) scientifically proved the brain cortex response to specific visual stimuli consisting of particularly oriented and sized lines and edges. In our view, “sign archetypes” (or re-workings?) had been retrieved, imprinted and re-worked by the primitive human mind by means of “metabolisation” of sensory-emotional perception, then becoming a “genetic indication” for acquisitions. Individual colours were also identifies in this way and these archetypes or re-workings are certainly contained in special dispositional representations connected with the “visual” areas of the brain cortex. The latter help us to recognise reality visually if they are recalled as mental images or they forcefully enter great artistic-pictorial expressions by means of the subconscious. Analogously, many linguists (Noam Chomsky, for example) argue that human language deep structure has much in common with brain structure, also reflecting its characteristics from the grammatical viewpoint. In our view, this is natural, seeing that brain cortex (the seat of the rational mind) structured itself on logical-rational abstractions of sensory-emotional perceptions, thus conditioning the very structure of spoken language.

Returning to visual perception and its implications (Maffei and Fiorentini 1995), psychologists studying painting from the mid 19th century onwards have posited various theories on the organisation of human visual perception and its application to art. The two most interesting ones are the constructivism and Gestalt theories. In the view of the constructivists, starting out from empirical philosophy, a visual image is, on each occasion, built up by means of a process of association of elementary visual sensations stored from birth in memory. This theory, which was especially developed by Helmholtz and Gregory argues for the descent of a visual image by way of continual (subjectively guided) comparison between the information supplied by the visual organ (the eye and adjacent nervous system) and the previously perceived images stored in memory. Each object coming into view is analysed by comparison with what has already been acquired by the senses and can (though not necessarily wholly) be recognised and accepted. This theory leaves responsibility for what has been perceived entirely with the observer and can be defined as “empirical cognitivism”.

The Gestalt theory, on the other hand, attributes visual perception to innate schemas, which are the same for all individuals (Kofka, Wertheimer and Kohler) and whose characteristics can be known and studied. This theory rejects the idea of visual perception as the sum of already stored sensations, thus broken down to them. Perception is the result of the organisation of innate sensations rather than association of empirically acquired sensations.

These two briefly described theories are applied to the analysis of artists’ works and both have points in their favour, in accordance with the sectors investigated.

From our point of view, we can immediately note the absence in either of them of any emotional content associated with visual perception, almost as though it flowed miraculously and automatically through the human brain without further implications and were stored in film like takes (constructivism) or retraced and understood following prefigured traces (Gestalt). The mistake is the same in both cases. Art is the starting point for the analysis of art and, consequently, hypotheses are formulated on the human perception and re-expression mechanism, instead of starting from human beings, their evolutionary history, their brain-nervous structure and, above all, the actual modalities of perception of reality only subsequently involving the visual system in respect of other perceptions (i.e. sound) and which thus cannot ignore what has already been imprinted by the other sensory acquisition centres. The same mistake was made in the case of music. Certain physicists and philosophers have studied the phenomenon of musical acquisition starting out from the laws of sound and the qualities of the ear, attributing the cause of “musical revelation” to the “non-linear” characteristics of hearing! “Non linearity” is certainly an important fact for identification of individual notes and harmonic-musical construction, and it is also certain that nature offers the “acquisition modalities”, which will then become a fundamental part of individual “technologies and methodologies of expression”, but it is not subservient to them nor does it make the human brain subservient. Sound without emotional-cerebral connection does not become “music”.

In our view, it is only by starting out from human beings that human creations (including artistic ones) can be understood. Moreover, so as to memorise something seen (independently of genetic predisposition), sensory perception is required that produces “emotion” and we will then be able to reconstruct reality (from the visual standpoint as well) by “emotional granules”, from which sign and/or colour archetypes (or re-workings) are extracted, or bring an artistic event to life. Sensory-emotional perception is never only “visual”. Seeing follows sound, and perhaps after touch, taste and smell. Gestalt “innateness” cannot be solely visual, but rather “all-embracing” or at least potentially so. It is impossible for us to conceive of a theory of “purely visible emotion” to study pictorial and figurative art.

8.6 An example of touch and visual generalisation

Correspondence between the gentleness and bitterness musical archetypes in human touch is evident. It is enough to stroke animal fur or a man’s cheeks a few hours after shaving (or any more or less soft surface): the gentleness archetype following the direction of hair or fur, the bitterness one up against it. If the interval between the two notes is in proportion to a longer distance to be covered over the same time, “decreasing gentleness” and “increasing bitterness” are perceived in accordance with the greater speed at which the finger moves along with or up against hair or fur.

Correspondence between these two archetypes in seeing and pictorial application leads us, as has already been noted, to observation of paintings with brush strokes with very close colour shades (with the greatest gentleness if there is decreasing pictorial-figurative “logic” with colours ranging from the darkest to the lightest, or with the least bitterness if there is increasing pictorial-figurative logic). However, these colour shades can gradually fall apart if “gentleness” diminishes and “bitterness” increases.

Correspondence could easily be found in the field of smell and taste, maybe by use of measuring apparatus (also applied to intervals).

As already mentioned, archetypes, which are initially only “musical” are supplemented and completed by means of the above perceptions as the senses are gradually acquired by the human body.

9.1 Archetypes and human personality

How do circumstances interfere with archetype acquisition? Here is an example: when a baby sees an animal (and perceives it as an independent entity) for the first time, it “assimilates” and acquires it in normal memory (acquiring the ability to “recognise it”) without actually “turning it into an archetype”. But if seeing this animal is linked with an unknown, abnormal situation, i.e. with a (more or less justified) “emotion” due to the latter, then the fear archetype comes to the fore and, if it has been previously imprinted and is due to other emotional perceptions, will appear again on sight of the animal or its image. If it has not been imprinted yet, this will happen for the first time in the mind’s deep rooted memory (by means of dispositional representations from innate circuits) beginning its archetypal structuring from this sight and not from a sound (cry), as we argued in the “musical” version of the same archetype. Subsequently, if the fear situation was unjustified, the mental cognitive part will require all its strength to break the chance, unexpected “tie” between the representation of the animal and the fear archetype!

If the above example is generalised for various situations and individuals, we will be shown how a particular, different perception/emotion association can contribute to the construction of a highly individualised “model of reality”. Now, human personality certainly has genetic presuppositions. Its structuring can be partially predetermined, but it is certainly influenced by the “individual model of reality” as formed by means of the various subsequent archetype acquisition modalities, which also influence the acquisition modalities of rationality, seeing that it derives from their “metabolisation”. In our view, this mixture stands at the origin of human personality, which will be gradually influenced by subsequent personal “histories”. We note that, though “primary emotions” (or archetypes) are the same for everybody, the archetypal chain deriving for the newly born human being from the series of acquisitions is absolutely different. This is a fundamental fact for structuring an individual personality, albeit in the environment of a predetermined genetic scheme. The archetypes following the first one are enclosed in inter-connected neuronal configurations (dispositional representations), which are influenced by the characteristics of the previous configurations. Acquiring the terror archetype after that of gentleness is something else, as acquiring it before. Naturally, all this is also reflected on the process of rationalisation of the emotions, for which the whole cognitive development of the mind can be influenced.

Actually, in agreement with all the schools of thought on child and developmental psychology, it is also our view that acquisitions in the earliest years of life are of great delicacy for human psychic development. We do not know whether there is genetic predisposition providing a subsequent acquisition methodology for the archetypes and various perceptions reaching the baby before and after birth. But there are certainly some paths to acquisition that are better than others. Everything that is less traumatic and has the lowest continuity solutions should be preferable.

10.1 Musical therapy

The archetypal hypothesis offers interesting possibilities for interpretation of musical-therapeutic effects (Revesz 1954, Valdeschini 1983, Lorenzini and Suvini 2001) observed in various kinds of patients.